Station life

In Australia, a large land holding used for livestock production is known as a ‘station’ – this originally referred to the main residence and outbuildings of a pastoral property but now generally refers to the whole land holding. Most stations are stock specific – classed as either sheep stations or cattle stations depending upon the type of stock raised – which is, in turn, dependent upon the suitability of the country and the rainfall. The owner of a station is known as a grazier, or pastoralist and, in most cases, Australian stations are operated on a pastoral lease.

> Find out more about the leasing of Pastoral Stations

Australian sheep and cattle stations can be thousands of square kilometres in area, with the nearest neighbour hundreds of kilometres away. Cattle stations in the inland regions of most states (excluding Victoria and Tasmania) can exceed 10,000 km²; Anna Creek station in South Australia (approx. 34,000 square kilometres or 8,400,000 acres) is the world's largest working cattle station. Such large, often unfenced, properties use mounted workers to tend livestock scattered across vast distances.

The role of mounted stockmen took on great importance in early nineteenth century Australia, following the spread of settlement into the interior of the continent after the successful 1813 crossing of the Blue Mountains. As farmers moved westward, many settled (or squatted) on huge selections of land, the rolling plains being ideal for grazing sheep and cattle. With the high value of early imported livestock, stockworkers needed to be trustworthy and self reliant, and good stockmen came to be highly regarded.

Australian aborigines played a large part in the successful running of many stations, especially in northern Australia. Using their local knowledge of the land, Aboriginal stockworkers became increasingly important after the gold rushes, when white labour was expensive and difficult to retain.

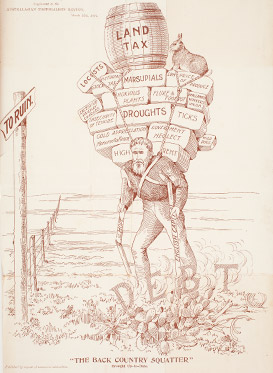

‘The Back Country Squatter : Brought Up-to-Date’, Australasian Pastoralists Review,

‘The Back Country Squatter : Brought Up-to-Date’, Australasian Pastoralists Review, March 15, 1897, chromolithographic print.

MF 3 R 12

All stock workers need to be interested in animals and handle them with patience and confidence. They need the skills to make accurate observations about livestock like judging an animal's age by examining its teeth, and experience in treating injuries and illnesses as well as routine care requirements such as feeding, watering, mustering, droving, branding, castrating, ear tagging, weighing, vaccination and dealing with predators.

Those caring for sheep must also deal with flystrike treatments, worm control and lamb marking. Pregnant livestock need special care in late pregnancy and stockmen may have to deal with difficult births. Apart from livestock duties, a stock person will also to inspect, maintain and repair fences, gates and yards damaged by storms, fallen trees, livestock and wildlife.

Station life continues with little seasonal variation beyond the occasional break in routine brought about by colt-breaking, mustering, cutting out, and branding. Then, all hands not actually engaged in boundary or outpost work assemble at the homestead, their ranks swelled by the arrival of the colt-breaker or the stock workers from neighboring stations.

Mustering on big stations used to mean long days spent in the saddle, camping out in isolated areas and sleeping in a swag (bedroll) on the ground – these days larger cattle stations use helicopters or light aircraft as well as stockmen mounted on horseback or motorbikes and trucks. Traditionally, stockmen used stockwhips and working dogs to herd stock together, driving them to holding yards or paddocks for drafting (ie. selecting stock out of a flock or herd) prior to branding, shearing or other routine care practices.

> Read stories about station life and stock workers in outback NSW

In Australia, a drover is typically an experienced stockman who may be an itinerant worker like the shearer. Droving is the practice of moving livestock, usually sheep or cattle, "on the hoof" over long distances in search of better feed and/or water during a drought, taking stock to market, or delivering animals to a new owner's property. While moving a small mob of quiet cattle is relatively easy exercise, moving several hundred head of wild station cattle over an unknown route is a highly skilled undertaking.

Station life can be lonely, especailly in remote areas, as accommodation for couples and families is limited. Consequently, many station employees are seasonal workers and often young. The jackaroo (male) or jillaroo (female) is typically employed on a station for several years, as form of an apprenticeship, in order to learn how to become an overseer or rural property manager. These days, as pastoral properties face recruitment shortages, and many young men are lured into the booming mining industry, female workers are a more common sight on outback stations.

This image viewer requires a web browser with the Flash plugin and JavaScript enabled.

Get the latest Flash player .