Station life

Settlers were required to take up their selections within five years of granting, and to improve and develop the land or face losing it.

George Townshend had received a land grant of 2,560 acres on 20 October 1826. He planted vineyards and fruit trees at Trevallyn and marketed his own brand of preserves. The 1830s saw a period of rapid agricultural expansion in the colony. Townshend went on a land buying spree, quickly building up a portfolio of ten farms in the Paterson River region.

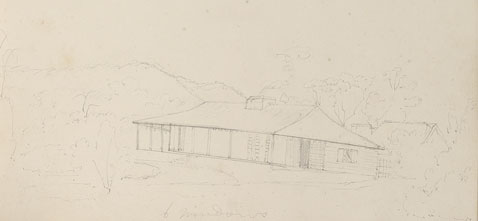

In October 1836 Trevallyn was visited by Conrad Martens, the celebrated artist, who was commissioned by Townshend to execute a painting of his home. Townshend was, himself, reputed to be a keen amateur artist and he was obviously impressed by Martens. In 1841, he stated that he owned five views of his property painted by Martens.

A severe drought and the subsequent economic depression saw Townshend lose nearly all of his County Durham property by 1845, with the exception of the Trevallyn estate which was in his wife's name.

[View of Trevallyn], 1837, by Conrad Martens

Watercolour DL Pg 54

Charles Boydell received an initial grant of only 640 acres and he was keen to earn more capital, and gain experience in colonial station management, before taking up his lease. Leaving George Townshend to keep an eye on his land, Boydell went to work as superintendent of a sheep run between Denman and Muswellbrook. He returned to Camyr Allyn in 1830 with an additional 640 acre grant and quickly set about improving his property.

Cam-Yr-Allyn, c. 1839, by Emily Manning

Pencil sketch PXB 524/43

In the years that followed, Boydell faced difficult conditions as he cleared the land, dealing with floods, a severe drought, life-threatening accidents and stark loneliness. He ran sheep and cattle on the property and planted wheat, corn, all kinds of fruit and vegetables and a vineyard. He attempted to set up a dairy and experimented with tobacco growing, before the local market surrendered to cheap American imports. He built a flour mill on the banks of the Allyn River and a dwelling suited to housing a future wife and family.

> Read Charles Boydell's fascinating journal entries about his life as a rural pioneer, 1830-1835

Detail from [Studies of Aborigines], c. 1838, by Emily Ann Manning

Pencil drawing PXB 524/26v

The Indigenous people at Camyr Allyn and Charles Boydell showed mutual respect towards each other. A peaceful coexistence developed between them which saw Boydell making use of traditional skills and Aboriginal people undertaking seasonal work for rations. Boydell was held in such high esteem that, as a great compliment, he was allowed to witness the funeral of Chief 'Jacky' in August 1833, an account of which is included in his journal - along with his record of the local vocabulary.

Detail from David, Prince of Alamongarindi, [Brass breastplate], 19th century

Engraved brass R 251c

Indigenous identities, recognised as tribal elders in regions where land had been taken up by white settlers, were often presented with inscribed metal plaques to hang around their necks. Commonly known as 'King' or 'Queen' plates, breastplates or gorgets, it is known that the Boydell's followed this tradition at Camyr Allyn. A brass breastplate was engraved with the name of the resident 'King' and, on his passing, this name was beaten out and the new king's name inscribed in its place - the Camyr Allyn plate had been engraved seven times when, on the death of the last king, it was returned to Mr James Boydell.

The breastplate shown is believed to have come to the Mitchell Library through a descendent of the Boydell family.

Detail from Views of Gresford and the Paterson River district, c.1880

Photographs

It's difficult to imagine the hardship entailed in clearing land without modern machinery, and the physical work required to keep a patch of cleared land fenced and maintained through manual labour. It is easy to understand the reliance upon ones' neighbours that developed in rural communities, pooling resources and working together at peak times of shearing, mustering and harvesting.