Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple Esq, July 26, 1794, drawn by Geo. Dance, etched by Wm. Daniell, 1802 Print P2 / 46

Alexander Dalrymple (1737 – 1808) was one of sixteen children born in New Hailes, Scotland, to an upper class family. At the age of fifteen, Dalrymple joined the British East India Company, and was posted to Madras, India. He travelled widely in Asia over the next thirteen years, visiting China and the East Indies, where he became passionately interested in trade, geography, astronomy, charting and exploration. He trawled libraries and offices looking for information and charts which related to discoveries in the Pacific and the history of European trading in the region.

Using the knowledge he had gathered about the history of exploration in the Pacific, Dalrymple started to build a hypothesis about the great unknown Southern continent. When he returned to London from South East Asia in 1765, Dalrymple used his sources to compile a book entitled An account of the discoveries made in the South Pacifick Ocean, previous to 1764 (first published in 1767). An account of the discoveries outlines Dalrymple's belief in the (hitherto) undiscovered Great Southern Continent and analyses the discoveries made on previous voyages to the South Pacific, primarily by the Dutch and Spanish.

An account of the discoveries made in the South Pacifick Ocean was read with interest by Joseph Banks. The book was particularly significant as the first account in English of the voyage made by Torres which had revealed the strait between Papua New Guinea and the north coast of New Holland. Dalrymple had learned of the discovery when translating some Spanish documents captured in the Phillipines in 1762.

> Read selections from An account of the discoveries made in the South Pacifick Ocean

By the time his book was published, Dalrymple had been elected fellow of the Royal Society, which was organising expeditions to various parts of the world to observe the Transit of Venus in 1770. One of the observation points lay in the Pacific Ocean, right in Dalrymple’s area of interest. He was desperate to take charge of this expedition, however the Admiralty would not give him charge of a vessel, as he was not qualified. In the end, command was given to James Cook, and Joseph Banks headed up the scientific observers. Both men made extensive use of Dalrymple’s book, and Cook’s route home took in the east coast of Australia and continued through Torres Strait.

Cook was carrying secret instructions to look for the unknown southern continent. One of Dalrymple’s hypotheses was that the known western coast of New Zealand may be the western coast of the giant landmass. By circumnavigating New Zealand, Cook disproved this, but Dalrymple wasn’t satisfied.

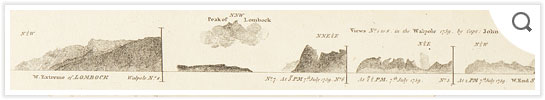

Chart of the South Pacifick Ocean, pointing out the discoveries made therein previous to 1764, by Alexander Dalrymple, [London : printed for the Author, 1770]

Printed map Q77/41

Still bearing a grudge against Cook for being passed over for the command of the Endeavour, Dalrymple insisted that Cook did not try hard enough to find the southern continent. He lambasted John Hawkesworth’s official account of the voyage in a published Letter from Mr Dalrymple to Dr Hawkesworth occasioned by some groundless and illiberal imputations in his account of the late voyages to the South (1773). His ‘Postscript to the Publick’ states:

‘The point is not yet determined whether there is or is not a SOUTHERN CONTINENT? although four voyages have been made …, at the same time I dare appeal…that I would not have come back in Ignorance.’

In 1775, Dalrymple returned to Madras for the British East India Company, despite having been dismissed by them in 1771 for being difficult and demanding. In 1779 he became the Company's hydrographer and published hundreds of charts. He remained argumentative and entered into many heated disputes over the correct names and locations of various Pacific islands. He theorised that trade with the people of the Pacific regions would be as lucrative as trade with India and China, as he believed that, like India and China, the Pacific was home to millions of asset-rich inhabitants.

In 1786 Dalrymple published A serious admonition to the publick, on the intended thief-colony at Botany Bay. He was convinced that the new penal colony was a cover for illegal trade, in defiance of the British East India Company’s charter ‘of exclusive trade and navigation’. Any European colony settled in Botany Bay ‘must have a view to New-Holland…It is obvious it must be very soon independent;…and very dangerous to England.’ He goes on to argue against the penal colony, suggesting that the remote Atlantic archipelago Tristan da Cunha would be a more suitable place for felons. His theories were nonetheless ignored by the authorities.

> Read selections from A serious admonition to the publick, on the intended thief-colony at Botany Bay

Dalrymple was appointed the Admiralty's first Hydropher in 1795. In this role, which he continued until his death in 1808, he is credited with the development of Admiralty Charts. Issued by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office, these nautical charts were contantly reviewed and updated in order that comprehensive and accurate maps of the world's oceans exist. Dalrymple’s legacy lives on in thousands of printed charts and maps - some published by him, some created by him, some created based on his work - many of which are held in the State Library of New South Wales.

> View selection of Admiralty Charts published by the Hydrographic Office

> Find maps and charts from the Library's collection of Dalrymple's Charts, 1771-1806

> Find Dalrymple's Charts via the Library's online catalgoue ![]()