The

fabric produced was often thick and cardboard-like, and had to be sewn together

when making skirts or loincloths. Bone or wooden needles were used, and

the thread was made from bark fibre.

‘Conserving

Curiosities’, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Though there are a variety of local names, the

word tapa, originally from Tahiti, is commonly used to refer to bark cloth made

all over the world.

Tapa Cloth, Museum of Natural and

Cultural History, University of Oregon

Many

of the pieces of tapa in Shaw's book are from Hawaii. These samples were

almost certainly brought back from Cook's third voyage.

‘Conserving

Curiosities’, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Hawaiian

barkcloth reached a high level of sophistication, due in part to the climate of

the islands, which was very suitable for the growth of the paper mulberry (Broussonetia

papyrifera) and the breadfruit (Artocarpus incisa), which were the

sources of the bark.

‘Conserving

Curiosities’, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

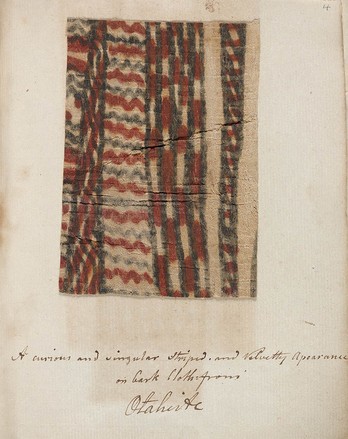

Dyes

and pigments were obtained from a wide range of sources, mainly from plants but

minerals such as red and yellow ochre were also used. Tapa was often

scented, with plants such as a fragrant fern (Polypodium phymatodes),

sandalwood (Santalum spp.) and ginger.

‘Conserving

Curiosities’, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Once

dyed, decoration was applied to the surface of the tapa in many ways.

Many of the Shaw barkcloth samples are decorated with bold geometric designs,

which were common in eighteenth century Hawaiian tapa.

‘Conserving

Curiosities’, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Documenting patterns and

cloth styles from eighteenth century Tahiti, Hawaii and Tonga, this unusual

work introduced Pacific tapa to the western world.

Back to list

Back to list