My father, Douglas Stewart, grew up in the New Zealand

country town of Eltham in the South Taranaki District on the west coast of the

North Island. As he described in his fishing memoir The Seven Rivers, seven trout streams tumbled to the seabetween Eltham and Opunake, 24 miles

away on the coast. Growing up in Eltham it was hard not to go fishing. There

were some like his father, Alec Stewart, and uncle Geordie Stewart (a visitor

from Melbourne) who preferred cricket; but most Eltham males, including the town’s

jeweller, the undertaker and my father, chose fishing.

At New Plymouth Boys’

High School where he was a boarder, the headmaster and sometimes the English

master, too, would sneak my father out of school to go fishing with them. His

English teacher also encouraged him to write poetry. As a consequence my

father’s first poem, ‘His First Trout’, soon appeared in the school magazine.

And so began the entwining of his two lifelong passions – poetry and trout

fishing.

In 1938, after a

six-month sojourn in England, he arrived in Sydney, aged 34, to take up the

position of assistant literary editor of the Bulletin. It was not long before he was also trout fishing at

Richards’ guesthouse on the Duckmaloi River, out from Oberon. By 1939, his

relationship with my mother, Margaret Coen, had also begun, and whenever he

stayed at Richards’ he wrote to her. Both his letters and a number of her

replies are held in the Mitchell Library. Reading them, it’s easy to see a

connection with the fishing map.

The whimsical and warm

correspondence is filled with ‘bird, beast & bug news’. My mother, who

spent her early years in Yass, NSW, had a particular love of nature’s oddities.

When her family moved to Randwick, Sydney, she kept a collection of Hairy Molly

caterpillars, all named after actresses, the prettiest caterpillar being Louise

Lovely. At school at Kincoppal convent, Elizabeth Bay, she was always in

trouble because of the contents of her desk, which housed an ever-increasing

accumulation of beetles, moths and lizards, live and dead, and even a specimen

preserved in a jar of mentholated spirits.

‘I haven’t yet managed to bottle for you any lugworms,

tapeworms, horse-stingers, bot-flies, bats, bits, hairy elephant flies,

ape-grubs, snukas, gazookas or palookas, but if you like I will send you

2,000,579,321 ordinary bush flies which live on the back of my coat & roost

in my ears,’ my father wrote jokingly to her from Richards’. With another

letter, he enclosed a sloughed, spotted snakeskin as a present for her. ‘If it

was not so fragile I would wear it in my hair,’ my mother responded, delighted

with the gift.

Writing to her again, my father concluded: ‘You are

everything that lives with grace in air or water and I miss you all chimes of

the clock.’ Because he was deemed medically unfit (twice) he did not fight in

the Second World War and the trout fishing letters continued throughout the war

years, giving ongoing evidence of their deepening intimacy.

My parents were married

in December 1945. For their honeymoon, they drove to the Duckmaloi in a

borrowed car. It was my mother’s first visit to Richards’ and one of the

hottest Decembers on record. She spent most of her honeymoon under the house

where it was coolest, reading Henry Handel Richardson in the company of the

Richards’ fowls that had also taken refuge there. But, despite the discomforts,

she relished the proximity to nature and painting subjects she found on a trout

fishing holiday. In two letters (also held in the Mitchell Library) written to

Norman Lindsay (with whom she had once been romantically involved), she

enthused about the countryside. The sights that thrilled her included a

princely sparrow hawk poised close on a branch and a skylark’s nest with three

brown speckled eggs in it.

I was born in 1948.

Although we had two family holidays on the Badja near Cooma in the early 1950s

and one at Kiandra in 1959, our association with the Snowy Mountains didn’t

really begin until January 1960 when we stayed three weeks at the Creel, a

guesthouse on the Thredbo River, some kilometres up from the straggling town of

Old Jindabyne on the road to Kosciusko.

The Creel had the smell

of trout about it. The regular guests and their garments had been so long

saturated with river waters and the viscous slime of fish that they almost

emanated trout. The verandah posts had special pegs on which the khaki-clad

regulars could unwind their waxed silk lines to dry out after a day’s fishing.

In the morning, amid much stomping of boots, there was a chorus of rich

creaking as lines were wound back in. A ritual adding of a shot of spirits to

pre-breakfast cups of tea also took place.

We returned to the Creel

for the next six summers, with the poet David Campbell, my father’s fishing

companion of many years, inevitably joining us for a few days. After the

guesthouse closed its doors in 1966, just before the site was covered by the

waters of Lake Jindabyne, we stayed further up the mountain at Sponar’s

Lakeside Inn and then later at a motel near the new township of Jindabyne.

My mother never fished.

Mostly she worked on landscapes in watercolour or drew near the car while my

father and I explored the streams with our rods. But every year for at least a

day or two she was struck down with a tummy bug that regularly assailed the

Creel’s guests (dead cows too close to the source of its drinking water was a

suspected cause) and chose to remain in the relative fly-free cool of the Creel

and paint there. Sometimes, too, with no upset stomach, she opted out of fishing

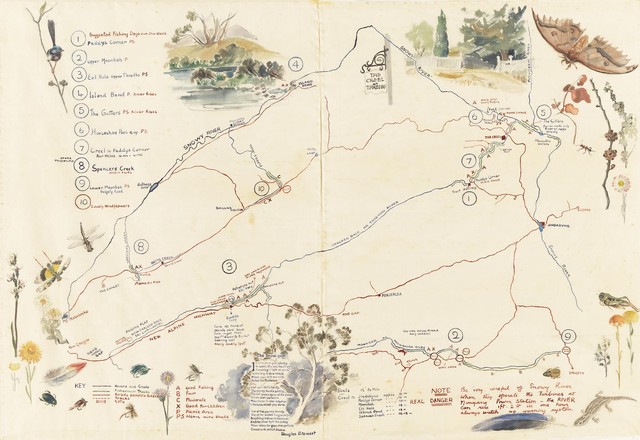

expeditions, just preferring a few days working on her own. On some such

retreat, she began the fishing map in one of the Creel’s big front bedrooms,

working from a rough guide on paper that had been handed onto my father.

She had begun painting on

silk in the late 1950s when she was given some specially prepared rolls from

Japan. She drew directly onto the silk with her brush, not using any pencil.

She had to be very skillful in the application of her paint. With works on

paper the paint can be moved around with water. But once it is applied to silk

there can be no changes.

My father and I regarded

the fishing map’s creation as quite magical. The surprise of what she had added

each day when we returned from fishing was a delight that added immeasurably to

that year’s holiday.

Back to list

Back to list