… Between

the ages of eight and sixteen, the males and females undergo the operation

which they term Gnah-noong, viz. that of having the septum nasi bored, to receive a bone or reed, which among them is

deemed a great ornament, though I have seen many whose articulation was thereby

rendered very imperfect. Between the same years also the males receive the

qualifications which are given to them by losing one of the front teeth. This

ceremony occurred twice during my residence in New South Wales; and in the

second operation I was fortunate enough to attend them during the whole of the

time, attended by a person well qualified to make drawings of every particular

circumstance that occurred. A remarkable coincidence of time was noticed as to

the season in which it took place, It was first performed in the beginning of

the month of February 1791; and exactly at the same period in the year 1795 the

second operation occurred. As they have not any idea of numbers beyong three,

and of course have no regular computation of time, this can only be ascribed to

chance, particularly as the season could not have much share in their choice,

February being one of the hot months.

On

the 25th of January 1795 we found that the natives were assembling

in numbers for the purpose of performing this ceremony. Several youths well

known among us, never having submitted to the operation, were now to be made

men. Pe-mul-wy, a wood native, and many strangers, cam in; but the principals

in the operation not being arrived from Cam-mer-ray, the intermediate nights

were to be passed in dancing. Among them we observed one man painted white to

the middle, his beard and eye-brows excepted, and all together a frightful

object. Others were distinguished by large white circles round the eyes, which

rendered them as terrific as can well be imagined. It was not until the 2d of

February that the party was complete. In the evening of that day the people

from Cam-mer-ray arrived, among whom were those who were to perform the

operation, all of whom appeared to have been impatiently expected by the other

natives. They were painted after the manner of the country, were mostly

provided with shields, and all armed with clubs, spears, and throwing sticks.

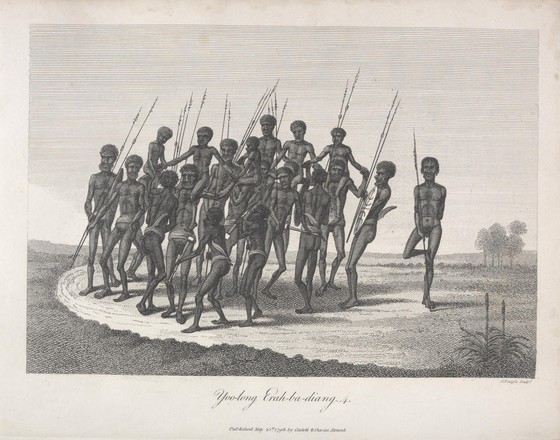

The place selected for this extraordinary exhibition was at the head of Farm

Cove, where a space had been for some days prepared by clearing it of grass,

stumps, &c.; it was of an oval figure, the dimensions of it 27 feet by 18,

and was named Yoo-lahng.

When

we arrived at the spot, we found the party from the north shore armed, and

standing at one end of it; at the other we saw a party consisting of the boys

who were to be given up for the purpose of losing each a tooth, and their

several friends who accompanied them.

They

then began the ceremony. The armed party advanced from their end of the

Yoo-lahng with a song or rather a shout peculiar to this occasion, clattering

their shields and spears, and raising a dust with their feet that nearly

obscured the objects around them. On reaching the farther end of the Yoo-lahng,

where the children were placed, one of the party stepped from the crowd, and

seizing his victim returned with him to his party, who received him with a

shout louder than usual, placing him in the midst, where he seemed defended by

a grove of spears from any attempts that his friends might make to rescue him.

In this manner the whole were taken out, to the number of fifteen; among them

appeared Ca-ru-ey, a youth of about sixteen or seventeen years of age, and a

young man, a stranger to us, of about three and twenty.

The

number being collected that were to undergo the operation, they were seated at

the upper end of the Yoo-lahng, each holding down the head; his hands clasped,

and his legs crossed under him. In this position, aukward and painful as it

must have been, we understood they were to remain all might; and, in short,

that until the ceremony was concluded, they were neither to look up nor take

any refreshment whatsoever.

The

carrahdis how began some of their mystical rites. One of them suddenly fell

upon the ground, and throwing himself unto a variety of attitudes, accompanied

with every gesticulation that could be extorted by pain, appeared to be at

length delivered of a bone, which was to be used in the ensuing ceremony. He

was during this apparently painful process encircled by a crowd of natives, who

danced around him, singing vociferously, while one or more beat him on the back

until the bone was produced, and he was thereby freed from his pain.

He

had no sooner risen from the ground exhausted, drooping, and bathed in sweat,

than another threw himself down with similar gesticulations, who went through

the same ceremonies, and ended also with the production of a bone, with which

he had taken care to provide himself, and to conceal it in a girdle which he

wore.

We

were told, that by these mummeries (for they were in fact nothing else) the

boys were assured that the ensuing operation would be attended with scarcely

any pain, and that the more these carrahdis suffered, the less would be felt by

them.

It

being now perfectly dark, we quitted the place, with an invitation to return

early in the morning, and a promise of much entertainment from the ensuing

ceremony. We left the boys sitting silent, and in the position before

described, in which were were told they were to remain until morning.

On

repairing to the place soon fater day-light, we found the natives sleeping in

small detached parties; and it was not until the sun had shown himself that any

of them began to stir. We observed that the people from the north shore slept

by themselves, and the boys, though we heard they were not to be moved, were

lying also by themselves at some little distance from the Yoo-lahng. Towards

this, soon after sunrise, the carrahdis and their party advanced in quick

movement, one after the other, shouting as they entered, and running twice or

thrice round it. They boys were then brought to the Yoo-lahng, hanging their heads

and clasping their hands. On their being seated in this manner, the ceremonies

began, the principal performers in which apperared to be about twenty in

number, and all of the tribe of Cam-mer-ray.

The

exhibitions performed were numerous and various; but all of them in their tendency

pointed toward the boys, and had some allusion to the principal act of the day,

which was to be the concluding scene of it. The ceremony will be found pretty

accurately represented in the annexed ENGRAVINGS.

Back to list

Back to list