Following the 1988 elections, the structures of the Aboriginal

Land Rights Act (ALRA) meant that Aboriginal people were less exposed to the

whims of government and equipped with a ‘war chest’ of sorts to challenge the

government’s agenda. And challenge

they did: in the court of public opinion and the courts.

While the Greiner reforms were unrealised the

changes to the Act that did eventuate radically changed the operations of the

land council and caused bitter division and enmity amongst Aboriginal

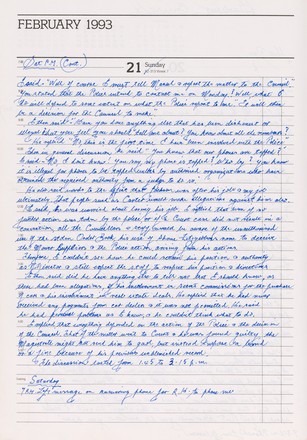

people. As Keane’s diary entries

reveal the bitter split between those who agreed with the changes and those

opposed to Greiner’s ‘deal’.

Once

in office the Liberals moved swiftly to implement their Aboriginal Affairs

reforms. Just four weeks into the new Government, in April 1988, the Premier

placed the existing Ministry for Aboriginal Affairs (MAA) under more direct

control of the Premier’s department, with Paul Zammit appointed Parliamentary

Secretary assisting the Premier.

In the first instance, plans to abolish the ALRA were blocked in the

Legislative Council.* The second attempt by the Government to

abolish the ALRA, via the appointment of an administrator to the NSWALC, was

also unsuccessful as there was insufficient legal basis to make an appointment.

The final and ultimately unsuccessful attempt by the Government was to

introduce an amendment to the Regulations of the ALRA that gave the government

power to take control of the assets and finances of the Aboriginal Land Council

network.

The

NSWALC lodged an injunction and proceeded to successfully challenge the

legality of the regulation. Thus,

litigation by NSWALC and lobbying of the cross-parties in the Legislative

Council stymied any immediate Government plans to dismantle the land council

network and control its assets.

But the Government’s influence over the operations of the ALRA

continued. Relocating the Aboriginal

Affairs bureaucracy to the Premier’s department meant that its officers,

including the Registrar of the ALRA and others in relevant departments,

variously pursued the Government’s agenda.

It

was in the Court of public opinion that the ALC and its ever-vigilant members

were most effective. By May 1990,

the Aboriginal Land Council network members had been in a sustained campaign

mode for two years against the Government’s varied efforts to dismantle and

then dramatically reform Aboriginal land rights in NSW. It was in this context that the newly

elected NSWALC Chair, David Clarke, came to approach Keane to work for the

NSWALC in a part-time advisory capacity. The elected Council were aware that the future of land rights

was in grave danger and the grass roots activism strategies that had been

effective in the past needed renewing.

The political negotiations of the elected Aboriginal leadership also

needed to step up a level.

The

campaign developed with the view to impressing the wider Australian public the

benefits of land rights for all

Australians. To this end from July 1990 the elected Councillors embarked on

a two-pronged strategy: an image-raising public relations campaign and a

massive parliamentary petition campaign.

Keane believed that ‘once the State Government realized that the Aboriginal

people were prepared and capable of mounting a campaign that would win public

opinion to their side, they would retreat from their hard line policy ... they

would begin the process of consultation to negotiate amendments which would be

mutually acceptable’.

By

September 1990, the NSW Government entered into negotiations with the Council

Chair David Clarke, to come to a mutually acceptable agreement. At a joint news

conference on 6 September the Premier and NSWALC Chair announced the details of

the agreed amendments to the ALRA Act.

The main change was that the regional tier was abolished and the

election process and tenure of Councillors was altered. They were to be directly elected with

full-time salaried positions instituted. Thirdly, land could be alienated.

While

generally viewed as a ‘back down’ from this more extreme position, the Greiner

amendments that eventuated contained a relatively simple but dramatically

transforming change to the ALRA land dealing provisions. Amongst other changes, they allowed for

land recovered under the Act.

These

changes saw a bitter divide emerge amongst land council members. Characterised

generally as pragmatists on one hand and those concerned with ‘grass roots’

community involvement.

But

the divisions went deeper still and reflect a naivety as well as vulnerability

on the part of elected representatives.

The Greiner changes saw much greater control concentrated in the state

office. At around the same time a

scandal unfolded that revealed corruption on the part of a senior

non-Aboriginal administrator know far and wide across the Aboriginal grapevine

as the ‘lawn mower affair’. In his

diary Keane meticulously documented the revelations by the senior bureaucrat

(subsequently investigated by the NSW Police and ICAC).

* The NSWALC effectively courted the support of the minority parties in the

Council. While the ALP, Greens and

Democrats had long supported the land rights movement, the support of the

right-wing Fred Nile led ‘Christian Democrat Party’ was less assured but one

which was secured by effective lobbying by key church affiliated members of the

Aboriginal community.

Back to list

Back to list