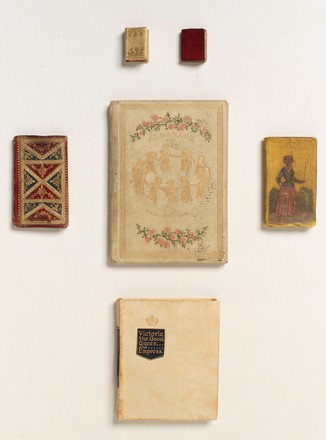

A selection of miniature books

1700s and 1800s

Bound volumes

The London Almanack: For the Year of Christ 1792

London: printed for the Company of Stationers, 1792

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 79/87

The London Almanack: For the Year of Christ 1765

Miniature book

London: printed for the Company of Stationers, 1765

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 76/11

Galileo a Madame Cristina di Lorenza,1896

Miniature book

Padova: Tip. Salmin, 1896

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 89/586

Schloss' English Bijou Almanac

‘poetically illustrated’ by S Lover’, 1840

Miniature book

London: A Schloss, 1840

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 84/456

Almanac for 1883

by Kate Greenaway

Miniature book

London: G Routledge, 1883

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE 88/649

Victoria, the Good Queen and Empress,1897

Miniature book

London: Gardner, Darton & Co, 1897

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 89/587

Bound volumes

The London Almanack: For the Year of Christ 1792

London: printed for the Company of Stationers, 1792

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 79/87

The London Almanack: For the Year of Christ 1765

Miniature book

London: printed for the Company of Stationers, 1765

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 76/11

Galileo a Madame Cristina di Lorenza,1896

Miniature book

Padova: Tip. Salmin, 1896

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 89/586

Schloss' English Bijou Almanac

‘poetically illustrated’ by S Lover’, 1840

Miniature book

London: A Schloss, 1840

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 84/456

Almanac for 1883

by Kate Greenaway

Miniature book

London: G Routledge, 1883

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE 88/649

Victoria, the Good Queen and Empress,1897

Miniature book

London: Gardner, Darton & Co, 1897

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

SAFE/ 89/587

These miniatures date from the 18th and 19th centuries, when miniature bibles, dictionaries and almanacs were the most popular editions. From the 19th century on, Children’s books, editions of Shakespeare and novels became increasingly popular, adding to the range of titles being produced in miniature form.

Although small in size, miniature books have had a big impact on the development of printing and bookbinding because of the exacting and intricate demands of their production. Miniature books require very fine paper, clear engravings and perfectly proportioned type. Binding requires particular skill and often included the production of a small carry in case with a magnifier.

Back to list

Back to list