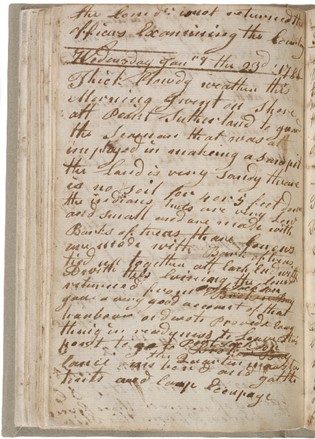

First Fleet journal

1787–93

Manuscript

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

DLSPENCER 374

Manuscript

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

DLSPENCER 374

John Easty’s original manuscript journal provides a rare and at times shockingly frank account of the earliest years of the colony. Much of our recorded history of the First Fleet and the first European settlement comes from official records and from the small minority of men and women of education and social status who kept journals. It is therefore particularly interesting to read the story of those early days in the blunt and untutored words of an ordinary soldier. Although some of his account was based on hearsay and some was written long after the events, we hear the voice of ranks other than officers and superiors.

Beyond this account however, we know little about John Easty. Neither his birth nor death dates are known. He probably served in France and Spain before being sent to NSW as one of the marine detachment in the First Fleet. Easty was appointed to Captain-Lieutenant Meredith's company on 4 November 1787. In December 1790 he was a member of two punitive expeditions sent against the Aboriginals around Botany Bay. He returned to England in December 1792 on the Atlantic, the same ship that conveyed Governor Arthur Phillip home. In September 1794 he was employed by Waddington & Smith, grocers, in London and spent some years petitioning the Admiralty for compensation for short rations in the years he was in NSW.

Back to list

Back to list