The Hillsborough was a large and roomy ship.

According to the Transport Commissioners, it had been fitted out on an improved

plan and the bars on the prison deck were spaced further apart to improve air

flow. Yet even during the trip from Gravesend, just south of London, to Portsmouth

one convict died and several became sick.

Sir John

Fitzpatrick, who had inspected the ship in the Thames, ordered the sick to be

transferred to a hospital ship, and urged most strongly that the ship's

complement of convicts should not be made up from the prisoners in the

Langstone Harbour hulks, aboard which the gaol fever, or typhoid, had raged for

some time. His advice was disregarded, as were his further protests. He

insisted, however, that five prisoners, all in an advanced stage of the

disease, should be disembarked, and all five died within a few days.

The Hillsborough sailed in a convoy from

Portsmouth on 23 December 1798, and at once ran into heavy weather. The

convicts' quarters were deluged and their bedding soaked. When the weather

moderated a few days later, a youthful informer told the captain that many of

the convicts were out of their irons and intended to murder the officers. Those

found out of their irons were flogged, receiving from one to six dozen lashes

each, and were shackled and handcuffed, some with iron collars put around their

neck. The allowance of rations and water was also reduced, so that for several

days the prisoners were half starved.

It is not

surprising that the disease carried aboard by the Langstone convicts spread

rapidly, and from the beginning of January 1799 deaths became alarmingly

frequent. Yet the convicts were kept closely confined and double-ironed, were

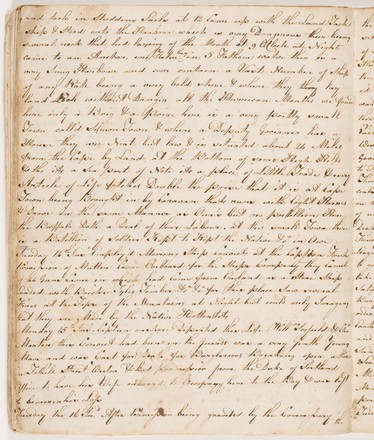

short of water, and were half starved. ‘It

was, one would think’, wrote William Noah, ‘enough to soften the heart of the most inhuman being to see us ironed,

handcuffed and shackled in a dark, nasty dismal deck, without the least

wholesome air, but all this did not penetrate the breasts of our inhuman

Captain, and I can assure you that the Doctor was kept at such a distance, and

so strict was he look after, that I have known him sit up till opportunity

would suite to steal a little water to quench the thirst of those who were bad,

he being on a very small allowance for them’.

According to

Noah, 30 convicts had died when the Hillsborough

anchored in Table Bay in Cape Town on 13 April 1799. There were then about 100

prisoners very ill. Although fresh provisions were served, deaths became so

frequent that the authorities were alarmed, and the ship was ordered to move to

False Bay. Noah alleges that to avoid further interrogation, the master buried

some of the convicts at the harbour entrance, but within a few days the bodies

were washed ashore. On 5 May, by which time at least 28 convicts had died since

the ship's arrival at Table Bay, the surgeon, J J W Kunst, returned from

Capetown with an order permitting the sick to be landed. When 146 were landed

the following day, they found that their hospital had previously been a stable

and was without a fireplace, windows and toilets, and next morning 56 of the

prisoners were returned to the ship. When the Hillsborough sailed on 29 May, at least 50 of the convicts had been

buried at the Cape.

When the Hillsborough reached Sydney, Governor

Hunter described the survivors as ‘the

most wretched and miserable convicts I have ever beheld, in the most sickly and

wretched state’.* Almost every prisoner required hospital treatment.

Footnotes

* Gov Hunter to Under

Secretary King, 28 July 1799, Historical

Records of Australia, Series 1, vol 2, 1797–1800, p 378

Back to list

Back to list