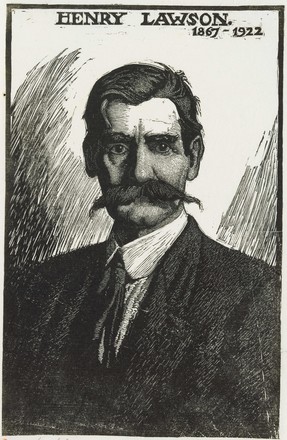

Portrait of Henry Lawson

1922

Woodcut on paper

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

DL PXX 85, Volume 10, 16b

Lawson’s was a sad, slow demise. He was one of Australia’s most acclaimed and cherished poets and writers, yet for many years he suffered from ill health, depression and alcoholism. On 2 September 1922, at the age of 55 he died of a cerebral haemorrhage.

Lionel Lindsay published this woodcut in the week Henry Lawson died. The print is based on a number of drawings that Lindsay made of Lawson some 20 years before, around the turn of the century when the two men first met. Lindsay had arrived in Sydney to work as an illustrator, and he and Lawson often contributed to the same periodicals that were published in Sydney, notably the Bulletin and the Lone Hand.

A clouded life

Henry Lawson was born on 17 June 1867 in the goldfields town of Grenfell in central NSW. He was the eldest of four surviving children of Niels Hertzberg (Peter) Larsen, a Norwegian-born gold miner, and his wife Louisa, née Albury, who was to make her own mark in history as a pioneering feminist.

As his family followed the promise of gold, Henry spent his childhood on the move. His introverted nature intensified when he suffered a sudden illness that resulted in a partial hearing loss at nine years old.By 14 he had lost almost all his hearing. The impact of deafness ‘was to cloud my whole life, to drive me into myself, and to be, in a great measure responsible for my writing’.*

At 17, Lawson was apprenticed as a coach-painter to a railway carriage-works company at Clyde, west of Sydney. During this time he began attending night school to improve his education. He also began writing his first poems. In 1887, Lawson began publishing his verse in the Sydney press, especially the Bulletin and Australian Town and Country Journal.

But by the early part of the new century, a failing marriage, mental instability and heavy drinking were taking their toll. Following a suicide attempt, Lawson spent several years in and out of sanitariums and gaol, arrested for drunkenness and for failing to pay child support. By now unable to look after himself and frequently found wandering the streets of Sydney, in 1908 he was taken in by poet Isabella Byers, who provided him with a home at Abbotsford and cared for him as his health and state of mind continued to decline. In 1920, Lawson was granted a £1 per week pension from the Commonwealth Literary Fund.

Footnotes

* Australian

Poetry Library, http://www.poetrylibrary.edu.au/poets/lawson-henry

So dense was the crowd

In honour of his ‘enduring and notable’ contribution to the nation,1 Henry Lawson was accorded a state funeral. The Argus newspaper reported on the events of that solemn day when Sydney turned out to farewell the beloved writer:

"The remains of Mr. Lawson lay in state at the mortuary chapel from early morning until noon, and in that time hundreds of people filed past the coffin for a last glance at the poet's face. Shortly after noon the coffin was removed to St. Andrew's Cathedral, where again there was a continuous procession of mourners until the service commenced. The Lieutenant-Governor (Sir William Cullen) sat in one of the front pews and near him were the Prime Minister (Mr. Hughes) and Ministers of both the Federal and State Governments. The chief mourners included Mrs. Henry Lawson (widow), Miss Bertha and Mr. James Lawson (children) … So dense was the crowd in George Street when the coffin was carried to the waiting hearse that it was some time before all the mourners could find their way to their carriages. As the cortege moved off, with troopers at its head, the Police Band, which preceded the hearse, played the Dead March in ‘Saul’. Through Paddington, Bondi Junction, and Waverley people lined both sides of the route almost continuously, and there were several hundred people waiting at the graveside in the Waverley Cemetery before the funeral arrived. As the poet's remains were lowered into the grave … Archdeacon Darcy Irvine lead the burial service, which concluded with the playing by the Police Band of ‘Abide With Me’."2

Footnotes

1. Sydney Morning Herald, 4 September 1922, p 8

2. ’Mr. Henry Lawson Buried’, Argus, 5 September 1922, p 10

The romance of the swag

‘The Australian swagman practises the easiest way in the world of carrying a load. I ought to know something about carrying loads: I've humped logs on a Selection, and loads of posts and rails and palings out of steep, rugged gullies (and was happier then, perhaps); I've carried a shovel, crowbar, rammer, and a dozen insulators strung round my shoulders with raw flax – to say nothing of soldering-kit, tucker-bag, billy and climbing spurs – all day on a telegraph line in New Zealand, often in places where a man had to manage his load with one hand, and help himself climb with the other; and I've helped drag telegraph poles up cliffs and sidlings where the horses couldn't go ...

The Australian swag was born of Australia and no other land – of the Great Lone Land of magnificent distances and bright heat; the land of Self- reliance, and Never-give-in, and Help-your-mate. The grave of many of the world's tragedies and comedies – royal and otherwise. The land where a man out of employment might shoulder his swag in Adelaide and take the track, and years later walk into a hut on the Gulf of Carpenteria [sic], or never be heard of any more, or be found in the Bush and buried by the mounted police, or never found and never buried –what does it matter … ‘*

Henry Lawson 1907, with Lionel Lindsay as illustrator

Footnotes

* FromThe Romance of the Swagman, by Henry Lawson, published 1907, Mitchell Library A823/ L425.1/ 8A1

Back to list

Back to list