Friends and rivals

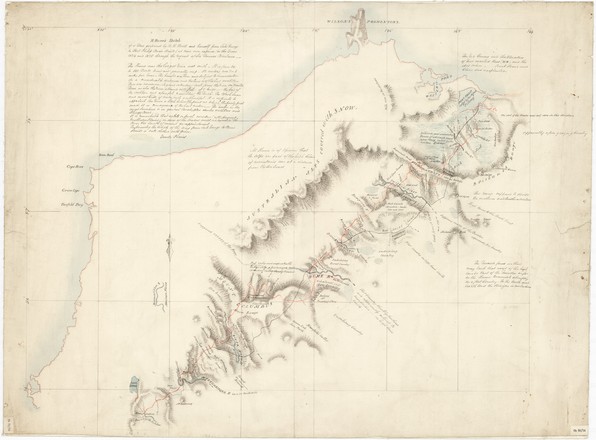

On 17 October 1824 Hume and Hovell and their party set off into areas not yet settled by the Europeans.

The expedition had to cross several treacherous rivers, including the Murrumbidgee. The Great Dividing Range also proved difficult. The bullocks had trouble keeping their footing on the steep, slippery mountainsides, and Hume and Hovell argued regularly about the best route through the mountains.

Hovell was older than Hume and probably used to being in charge. He also had extensive navigational experience from his sailing days. Hume, on the other hand, was arrogant, but knowledgeable about bushcraft and the Australian landscape. At one stage, the expedition split in two, because the men could not agree on the direction to follow. But Hovell soon rejoined Hume when he realised that his partner was right, and the expedition proceeded in a relatively friendly fashion. Ironically, most of the credit for the expedition went to Hovell, as the older partner, but it appears now that Hume, with his superior knowledge of the bush, may have contributed more to the success of the expedition.

On their return in January 1825, Hume and Hovell reported their discoveries to Governor Thomas Brisbane. A party was sent by sea to Westernport to re-examine the fine land which Hume and Hovell had described, and it was then that Hovell realised that they had journeyed to Corio Bay in Port Phillip, not Westernport, as he had previously thought. Despite this error, Hume and Hovell's expedition opened the way for settlement around the Port Phillip area, resulting in the founding of Melbourne.

Both Hume and Hovell were rewarded with large land grants, but later a bitter dispute erupted between the two men over their respective roles in the expedition. In an 1853 visit to Geelong, Hovell was celebrated as the discoverer of the region, and the press reports enraged Hume, who thought that Hovell was claiming sole credit for their discoveries. Both men published pamphlets giving their versions of the expedition. Hume remained embittered until his death in 1873.

Happy within themselves

During his explorations, William Hovell regularly recorded encounters with the local Indigenous people, commenting on their methods of food gathering, tools used and land management techniques, such as grass burning and damming of rivers to catch fish. He seems to have been respectful and perhaps a little envious of their ability to live in a landscape he found hostile. One journal entry states:

"Those are the people we generally call ‘miserable wretches’, but in my opinion the word is misapplied, for I cannot for a moment consider them so. They have neither house-rent nor taxes to provide, for nearly every tree will furnish them with a house, and perhaps the same tree will supply them with food (the opposum). Their only employment is providing their food. They are happy within themselves; they have their amusements and but little cares; and above all they have their free liberty".*

Footnotes

* Journal of William Hovell, 29 November 1824, State Library collection, Safe 1/ 32d

Back to list

Back to list