Portico Doors

Donated by Sir William Dixson in memory of David Scott Mitchell, 1942

Inspired by the style of doors that graced the entries of some of America’s most significant public buildings, the bronze portico doors illustrate various elements of Australian history. The central doors honour European explorers of Australia; the left side shows the navigators who explored Australia’s coast and the right side, the explorers who travelled inland (the individual panels identify each explorer by name). The reliefs on the bordering doors were originally planned to depict the various arts and sciences represented in the Library’s collection, but the principal librarian William Ifould rejected the concept in favour of panels illustrating scenes from the lives of Australian Aboriginal people.

Planning for the doors began in the early 1930s, however Ifould’s vision for ‘a beautiful pair of bronze entrance doors’ quickly became embroiled in controversy. Much debate focused on the subject matter, particularly the Aboriginal panels, which some thought should feature portraits of governors. The process also came under fire. Ifould’s tight control was criticised in the press, with comments that the artists should be selected by public competition, while a perception that an enemy-alien had been chosen to create the central doors was seen as outrageous (Arthur Fleischmann was in fact Slovakian born). The cost of the doors was also criticised, with many arguing that the money would be better spent on home defence.

Taking advantage of the opportunity

"… on Saturday Morning I found Mr Dixson looking for me for a game of golf at Killara. After missing a six-inch putt in order that he should have the pleasure of squaring the match with me on the last green, I found him in a very good mood. After the usual whisky and soda, I took advantage of the opportunity and his mood to broach the subject [of the portico doors] and he said ‘How much would it cost?’ I said ‘Somewhere about 3000 pounds’ and he said, Well I am prepared to stand up to it to the extent of, say, 4000 pounds if it is necessary to pay that much."

Principal librarian William Ifould, c1934

Footnotes

D J Jones, A Source of

Inspiration and Delight, 1988, p 86

… and more to the south

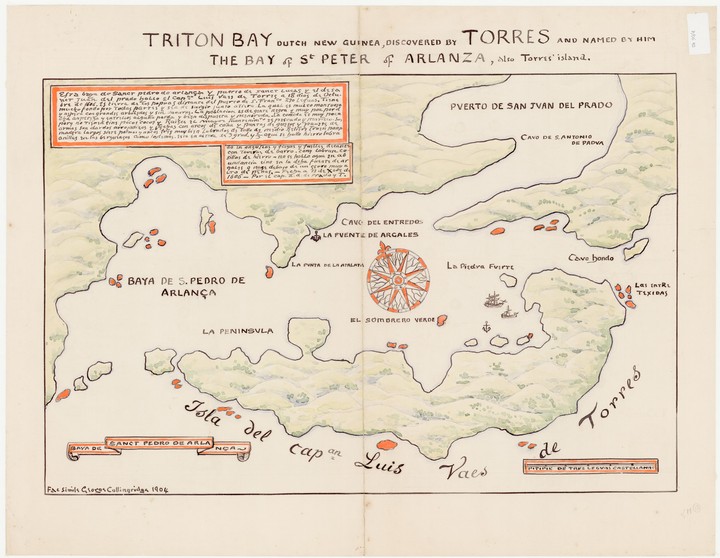

The 19th-century

writer George Collingridge claimed that Luís Vaz de Torres (top left on the

central doors) ‘had discovered Australia without being aware of the fact’.1

While en route from Spanish Peru to Manilla in 1606, the maritime explorer

charted the coast of New Guinea, showing it was separate from the still

mythical great southern land. In his report to the Spanish king, Torres noted, ‘Here

there are very large islands, and more to the south’.2

Following the British invasion of the Philippines in 1762, documents

from the expedition were translated into English and fuelled further

exploration of the region. The waterway south of New Guinea was named Torres

Strait in his honour in 1769.

Footnotes

1. George Collingridge, The First

Discovery of Australia and New Guinea, 1983 (first published 1906)

2.Translation of Torres’s report to the king in George

Collingridge, The First Discovery of

Australia and New Guinea, 1983 (first published 1906), pp 229–37

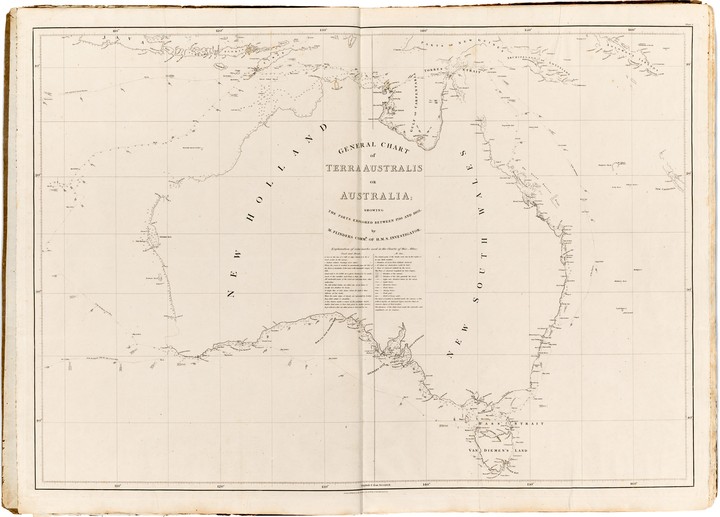

Bass and Flinders

George Bass and Matthew Flinders (bottom row left on the central doors) shared a passion for the sea and quickly became friends after meeting during their voyage from England to Australia on board HMS Reliance. Only weeks after arriving, Bass and Flinders set out to explore the new colony in a tiny 2.5 metre boat nicknamed Tom Thumb. During the nine-day adventure they explored and mapped Botany Bay and its inlets, which led to the British discovery of the George’s River, where the settlement of Bankstown was founded. Many adventures along the south coast followed, including to Shellharbour and Port Hacking.

Following the coast further southward, the currents, winds and tides convinced Bass that Van Diemen’s Land (present-day Tasmania) was separate from mainland Australia. However it wasn’t until their journey aboard the Norfolk in 1789–99 that Bass was able to prove his theory correct. Governor Hunter named the body of water between the two islands in his honour.

Back to list

Back to list