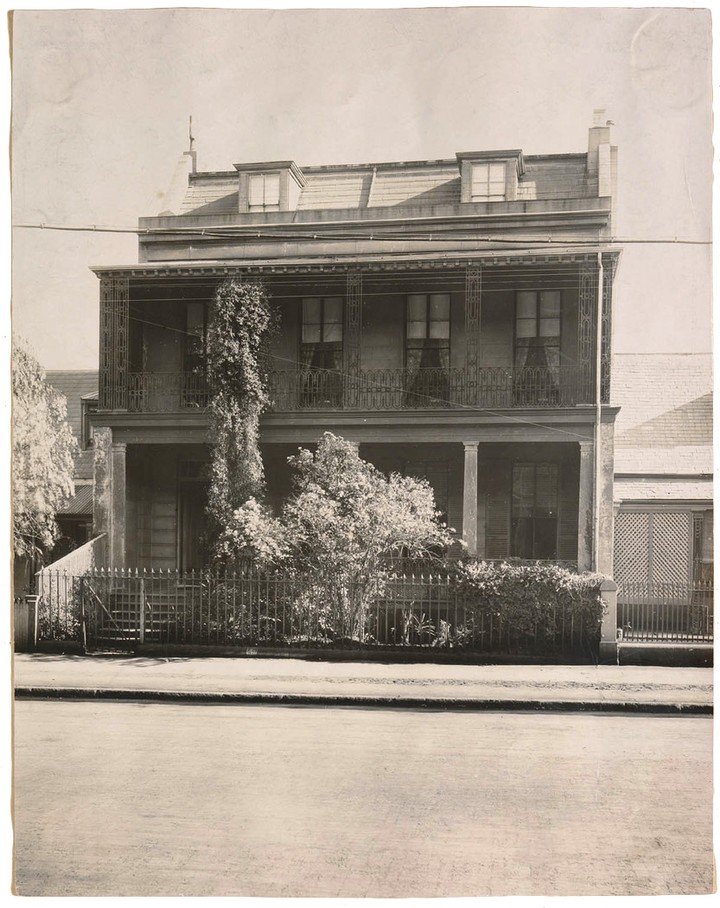

Mitchell Library

c.a. 1910

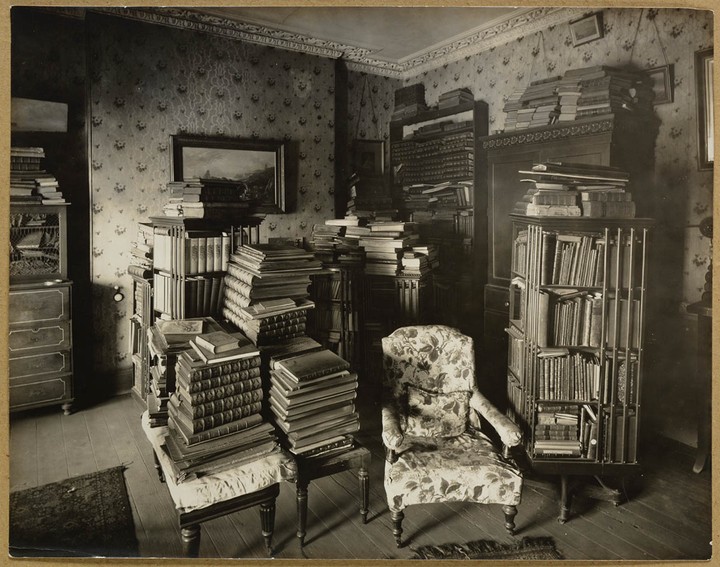

‘ … The story begins, of course, with David Scott Mitchell’s bequest, which included not only his collection, but in part his character as well. As book dealer Fred Wymark recalled, Mitchell “started collecting books and at the last the collection collected him and held him in such a grip that he became a part of his own collection”. Mitchell didn’t simply acquire. He actually knew his collection, impressing visitors with an astonishingly detailed knowledge of it which he gladly shared.’ – State librarian Regina Sutton, 2010 [1]

Promised in 1898, Mitchell’s bequest came with the condition that ‘a special wing or set of rooms’ be provided to house the collection [2] – and came at a time when the Library had already outgrown its existing premises on the corner of Bent Street. After a string of delays and setbacks, work on a new building finally began in 1906. The sandstone façade with pilasters and hood-moulds above the windows reflected late Renaissance architecture. The grand framework’s interior featured reading rooms, work areas and galleries, and was fitted out with state-of-the art steel bookshelves, electric built-in table lamps, oak swivel chairs and heavy teak tables. Then president of the Library’s Trustees, Prof Mungo MacCallum, described the building by saying ‘we have here a worthy shrine for Mr. Mitchell’s gift’ [3]. Mitchell, however, had died on 24 July 1907, only months before the building was completed.

The Mitchell Library officially opened in 1910 and in 1929 was extended to the south with the addition of the Dixson Wing. This enabled storage and gallery space for the extensive collection of historical paintings presented by Sir William Dixson. In 1939 work began on the central portion of the building, which included the portico, the ornate vestibule and a splendid new main reading room for the Public (now State) Library. The Public Library, located on the opposite corner of Bent and Macquarie streets, had outgrown its early 19th-century premises. As the additions were completed in June 1942, both the Public Library and Mitchell Library were at last united under one roof. In 1964 the south-east wing, facing towards Hospital Road, the Domain and Parliament House, was added containing additional storage areas.

Mitchell believed passionately that it was important to inspire Australians to develop an interest in the origins of their culture. He claimed that ‘the main object of his life’ had been to enable future historians to ‘write the history of Australia in general and New South Wales in particular’ [4]. His gesture not only laid the foundation for the Mitchell Library’s creation and direction but has also influenced many other donors and supporters to contribute to this institution.

Timeline

1929: The Dixson Wing opens.

1942: The central wing is built to house the public library and unite the Mitchell and Public libraries on the one site. The additions facing Shakespeare Place along with the extensions to the north and east, which include the portico, General Reference Library (now known as the Mitchell Library Reading Room), Shakespeare Room, vestibule and Tasman map are completed.

1959: The Dixson Library and marble staircase are built.

1964: The south-east wing is completed.

1988: The Macquarie St Wing is completed and minor refurbishments are made to the Mitchell Wing.

2001: Major refurbishment of the 1942 Reading Room is completed.

Footnotes

1. One hundred: a tribute to the Mitchell Library, 2010, p 5

2. D J Jones, A Source of Inspiration and delight, 1988, p 38

3. Jones 1988, p 50

4. B H Fletcher, Magnificent Obsession, 2007, p 34

Back to list

Back to list