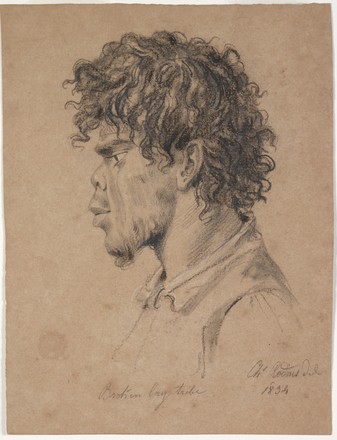

Broken Bay Tribe

1834

Pencil and charcoal on paper

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

DL Pd 43

Pencil and charcoal on paper

Bequest of Sir William Dixson, 1952

DL Pd 43

Entrepreneurial in nature, Charles Rodius found a ready market among successful colonists for his elegant, technically sophisticated and often flattering portraits. Portraiture was a primary source of income for colonial artists: as one newspaper noted in 1847, when commenting on the local art scene: ‘self predominates in the orders given for portraits, ships, and “my horse”, and “my house” make up the subject of all the pictures, and vanity pays for these at a reasonable rate’[1]. Rodius also found unusual ways of expanding his business, advertising that ‘in the event of the loss of deceased friends or relatives’, he would, ‘produce a likeness after death capable of supplying affection’s broken link in the memory of the survivors’[2].

It seems that Rodius made portraits of Aboriginal people of the Sydney region to sell to travellers eager for images of the ‘curious’ original inhabitants of Australia or, as the Sydney Gazette noted, to locals wanting souvenirs to explain their new home to ‘friends in England’. The Sydney Herald of 2 October 1834 commented on the ‘extraordinary fidelity with which the characteristic countenance of these sable children of nature are delineated.’ Indeed, Rodius’ portraits often show a sensitivity and complexity that belies the simplicity of the materials used. Made at a time of widening dispossession, discrimination and terrible conflict between the colonists and Aboriginal people, Rodius’ portraits also seem remarkably composed.

Back to list

Back to list