The price of PEACE

The most enduring institution

in Aboriginal–European relations — the annual distribution of blankets —

produced valuable documents for Aboriginal family and social historians.

Although often attributed to

Governor Macquarie, the annual distribution of blankets was initiated by Governor

Darling in 1826. Conflict at Bathurst and in Argyle County, near Goulburn,

early that year led Darling to act on a request from Bathurst magistrates and

order distributions of blankets and ‘slop’ (cheap ready-made) clothing to

Aboriginal people in several districts. He requested that magistrates identify

Aboriginal leaders who could assist in the capture of bushrangers and

communicate Aboriginal grievances so that future conflict might be prevented.

A letter in the Mitchell

Library from Argyle magistrate David Reid — written in October 1826 in response

to Darling’s request — contains an observation that would lay one of the

foundations of the annual distribution of blankets:

With

respect to slop clothing, it is decidedly my opinion that Blankets are the only

articles which would prove useful to them … for these they would do anything.

The first general

distribution of blankets and slops took place across the Nineteen Counties of

the colony on 23 April 1827, the King’s Birthday. Although the process soon

descended into complete confusion, the Aboriginal reaction was most

instructive. People began to move towards Parramatta and Sydney to demand the

promised blankets. It was not until 1829 that the distributions were properly

organised and limited to blankets.

Blankets played a crucial

part in negotiations with the Aboriginal people who had waged a campaign of

resistance in the coastal ranges of St Vincent County in 1830. When they

demanded to be included in the scheme, Darling readily agreed and conflict

ceased. Local settlers such as William Turney Morris, who had called for the

usual military action against the Aboriginal people, now competed to be

appointed agents for blanket distributions, which were seen to offer ‘security

and convenience’. In 1832, Morris distributed blankets at his Mooramoorang

station and compiled the census of the district’s Aboriginal population that is

now part of the Mitchell Library collection.

Morris’ ‘Return of

Aboriginal Natives’ is typical of the census returns distribution agents were

required to submit between 1828 and 1844. They recorded each Aboriginal man’s

English name, native name, probable age, number of wives and children, tribe

and district of usual resort. While they often providethe earliest written

records for Aboriginal family historians, the returns have limitations. They

were gathered only in the colony’s Nineteen Counties (an area reaching

Wellington in the west, Port Stephens in the north and Batemans Bay in the

south), Twofold Bay and Port Macquarie. Many agents failed to complete the

required census returns or used them to record only those who received

blankets, which sometimes meant women and children’s names were recorded but

relationships were rarely noted. The spellings of names varied from year to year,

and ages were very ‘probable’.

Darling had issued 626

blankets in 1831; under his successor, Governor Bourke, the number reached 2160

by 1835. The success of the scheme, however, was underpinned by the willingness

of Aboriginal people to participate. By issuing blankets, the colonists had

unwittingly chosen an item which, in its traditional skin rug form, was a

potent element of Aboriginal gift exchange. David Dunlop, magistrate at

Wollombi, explained it thus:

any

encroachment on each other’s boundaries occasions much hostile feelings betwixt

the tribes. Sometimes the price of peace must be either a young gin, or an

opposum cloak … Their simple nature understood it thus, that the Governor sold

their grounds to people … and that in lieu thereof he gave blankets.

By participating in the

annual distribution of blankets, Aboriginal people sought to contain the

overwhelming European threat, restore some semblance of order to a world now

shared with Europeans, who were at least meeting some traditional obligations,

and ensure a measure of security for themselves. Their hopes proved

illusionary.

In 1844 Governor Gipps

abolished the annual blanket distribution. Aboriginal people within the

Nineteen Counties were no longer a military threat, and the effects of disease

and dispossession had made them dependant on blanket distributions. Gipps had

not witnessed the blanket diplomacy of the 1830s. Instead, he saw only a

thriftless and powerless people receiving ‘indiscriminate charity’.

Nevertheless, Aboriginal

people maintained their belief that blankets were their right. Many local white

officials and clergy also supported the distributions. In 1848 Governor FitzRoy

responded to appeals and restored the annual distribution of blankets in

settled districts. In subsequent years, it expanded to apply to all Aboriginal

people in the colony. However, neither Aboriginal people nor white supporters

saw blankets as sufficient recompense for Aboriginal losses.

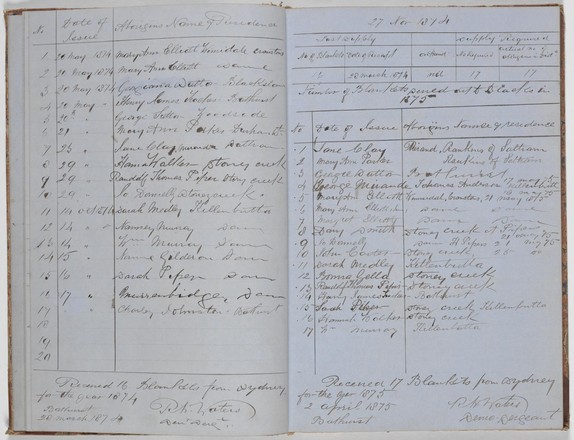

From this time, blankets

were usually distributed by police at local police stations or courthouses.

They were supposed to be issued on the Queen’s birthday, but this was often

impractical. Police recorded the names of Aboriginal people who received

blankets, and some lists have survived in a ledger held in the Mitchell

Library. The ledger contains the names of Bathurst Aboriginal people, their

home locations and the dates in the 1860s and 70s when they received blankets —

often not on the Queen’s birthday. By this time, these Aboriginal people had

adopted standard European surnames in addition to their Aboriginal names,

greatly assisting family historians in tracing their ancestry.

Aboriginal attitudes towards

blanket distributions changed after the 1880s as blankets became a tool of

control in the hands of the Aborigines Protection Board. Economic austerity

during the First World War provided the Board with the opportunity to stop the

annual gift of a blanket to every Aboriginal person, which had cost the

government £3734 in 1913. The distribution of blankets was restricted to

indigent persons, and by 1962 it had been subsumed by the wider welfare system.

In this way, the annual distribution of blankets to Aboriginal people faded

away. It is remembered, not as an attempt to achieve security through

reciprocity, but as a symbol of paternalism and dependency.

Author:

Historian Michael Smithson

completed a thesis on the annual distribution of blankets in NSW and has

written on the Aboriginal history of the Braidwood district.

Back to list

Back to list