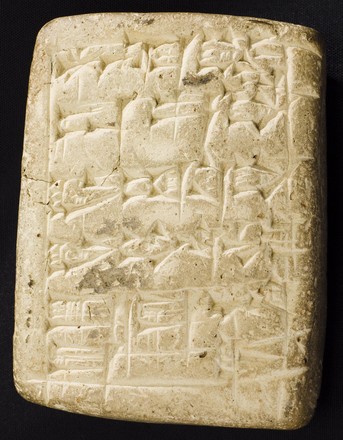

The

State Library of New South Wales in Sydney has a tablet in its Rare Books

collection. According to the records of the then Principal Librarian, William

Herbert Ifould, OBE, the tablet was donated to the State Library on 21 February

1940 by Mr J Yared who had migrated from Syria and was then a resident of

Maryborough in Queensland. At the time it was thought to be a replica, but

inspections by Dr Noel Weeks in March 1975 and Dr Larry Stillman in August 1983

identified the tablet as genuine.

The

inscription is in Sumerian and dates to the reign of Sîn-kašid (c1860 BCE) who

ruled the city of Uruk, located in the south of modern-day Iraq. The tablet was

baked, which is a significant factor in its excellent state of preservation. The

inscription records the king’s name, titles and epithets and states that he

built a royal palace. There are many other known examples of this inscription recorded

on a variety of objects, including bricks and clay cones.

It

is certain that this artefact was once among the many similar tablets and clay

cones bearing this inscription that were recovered from the foundations of

Sîn-kašid’s palace at Uruk. These objects functioned as foundation deposits and

were placed on every fourth course of bricks during construction. The purpose of doing so was to ensure that when the mud-brick palace needed

renovation over the future centuries, Sîn-kašid’s name and deeds would be read

by his successors and his legacy would survive.

Bibliography

D

Charpin, DO Edzard, and M Stol, Mesopotamien:

Die altbabylonische Zeit (Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 160/4), Academic

Press Fribourg, 2004

RS

Ellis, Foundation Deposits in Ancient

Mesopotamia (Yale Near Eastern Researches 2), New Haven: Yale University

Press, 1968

D

Frayne, Old Babylonian Period (2003 –

1595 BC) (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Early Periods 4), Toronto:

University of Toronto Press, 1990

AR

George, House Most High: The Temples of

Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations 5), Winona Lake:

Eisenbrauns, 1993

AR

George, Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and

Related Texts in the Schøyen Collection (Cornell University Studies in

Assyriology and Sumerology 17 / Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collections

Cuneiform Texts 6), Bethesda: CDL Press, 2011

Back to list

Back to list