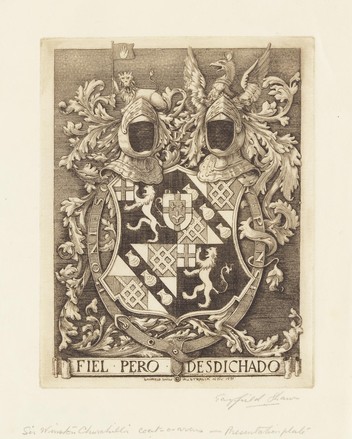

Australia has honoured the Briton's

memory, though he was never particularly fond of this country.

Sir Winston Churchill, twice prime

minister of Britain, holder of many other great offices of state between 1905

and 1955, regarded by many as the saviour of his country for his heroic

leadership during World War II, died on January 24, 1965, just half a century

ago.

His death occurred on the 70th

anniversary of Lord Randolph Churchill's passing. Lord Randolph, the father

whose affection Winston had craved, died a disappointed man and a failed

politician.

When

he spoke in cabinet about 'the troublesome attitudes of the colonies', it

seemed Australia was the chief offender.

His son, by contrast, was "the man

of the century". The first prime minister of Britain to receive a state

funeral since William Ewart Gladstone, a political rival of Lord Randolph's,

back in 1898, Churchill's body lay in state for three days. In bitterly cold

weather, more than 300,000 people passed through Westminster Hall to pay their

respects. The Queen and other members of the royal family attended the funeral in

St Paul's Cathedral. Five other monarchs came, and more than 20 heads of state.

Churchill's death had long been

expected. Even during World War II itself, he had suffered heart attacks and

strokes. His second prime ministership, 1951-55, was interrupted in 1953 by a

massive stroke from which few thought he would recover. After leaving office in

1955, he declined slowly, confiding on one occasion that "life was over

but not yet ended".

A member of the House of Commons until

1964, the British election of that year was the first in the 20th century at

which he had not been a candidate. When he celebrated his 90th birthday on

November 30, 1964, 70,000 people sent messages, more than double the number who

had done so on the occasion of his 80th birthday.

His birthday appearance at the window

of his home in Hyde Park Gate to acknowledge the cheers and singing of

well-wishers was his last public appearance. But it was not his last

engagement; that occurred on December 10, when he dined for a final time at the

Other Club, a dining group he and others founded more than half a century

earlier after they had been excluded from more demure gatherings on grounds of

excessive rowdiness.

A stroke on January 10, 1965 was the

beginning of the end. Thereafter he drifted in and out of consciousness. The

public was first alerted six days later. A medical bulletin reported that

"after a cold Sir Winston Churchill has developed circulatory weakness and

there has been a cerebral thrombosis".

The Canberra Times' headline shortly informed readers: "Churchill sinking, but

clings to life." Another headline said simply that he was "near

death". On January 25, readers learnt Churchill had died "peacefully

in his sleep ... a strange hush seemed apparent almost everywhere". The

editorial was headed: "The greatest man of his age".

Australia's prime minister, Sir Robert

Menzies, was on the other side of the Pacific as the news reached Australia.

Following a half-Senate election campaign, he had boarded the P&O liner

Arcadia for several weeks' vacation. Leaving the ship in Los Angeles, he flew

to London as chief representative of the nation in a group which included the

former prime minister, Lord Bruce, a Gallipoli veteran (though with a British

regiment).

Another Australian representative was Lord

Casey, an Anzac veteran. He first met Churchill on the western front in 1916,

later serving as British minister in the Middle East, 1942-44, and as governor

of Bengal. The opposition leader, Arthur Calwell, was also cruising the

Pacific. He had just arrived in Auckland and decided that distance prevented

his attendance.

Menzies was appropriately chosen as

Commonwealth representative among the pall-bearers; the others were drawn from

the great and the good in Westminster and Whitehall, and sundry lofty figures

from the armed services.

Among the democracies represented,

Menzies alone had dealt with Churchill on a head of government basis during the

war's early days. Indeed, when Menzies became prime minister in April 1939,

Churchill was still in the wilderness.

Many others present, including newly

elected prime minister of Britain Harold Wilson Canadian prime minister Lester

Pearson, former US president Dwight D. Eisenhower and French president Charles

de Gaulle had been, during the early years of war, only in staff posts of

varying significance.

After the funeral, from the crypt of St

Paul's, Menzies made an eloquent and justly famous speech: "I lived in

Churchill's time."

Before leaving London he joined in

launching the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust. A Commonwealth-wide scheme, its

purpose was to provide opportunities for people from all walks of life to study

and travel abroad. Upon returning to Australia, details of the national scheme

were announced, with Menzies as president and the other two party leaders, John

McEwen (Country Party) and Arthur Calwell (Labor), as vice-presidents.

Sunday, February 28, was designated

Churchill Sunday. A nationwide door-knock mainly organised by the RSL yielded

nearly £1 million, which meant that, with contributions from governments and

corporations, Australia raised double the targeted sum, a performance unmatched

elsewhere in the Commonwealth.

Herein is the irony, the paradox, the

mystery. For, of all the self-governing dominions it was, throughout his

career, with Australia that Churchill most frequently locked horns.

In his earliest days as a minister he

sought, unsuccessfully, to block Deakin's invitation to President Theodore

Roosevelt for the US Great White Fleet, as it cruised the Pacific, to include

Australia. Within a decade he had a very major hand in the Gallipoli campaign,

a conflict which, even in the late 1950s, according to celebrity researcher Ann

Moyal (who knew him), "still haunted him".

In the 1930s and early years of World

War II, Empire defences in the Pacific were a major source of friction.

Australian participation in the ill-fated Greek campaign was another source of

contention.

After Japan entered the war, relations

reached a low ebb over, first, recall of Australian troops from the Middle

East, and then Churchill's attempt to divert the troop convoys to Burma. In

these tense times he noisily complained that nothing much better could be

expected from

"bad stock". When he spoke openly in cabinet meetings about "the

troublesome attitudes of the colonies", it seemed that Australia was the

chief offender. In his second prime ministership he struggled, again without

success, for incorporation of Britain within the ANZUS Pact.

Churchill never visited Australia: he

once told his doctor that "they want me to go to Australia and New

Zealand, but I haven't the heart or strength or life for it". One

historian has observed that Churchill's name and image was the "source of

division in Australian party politics" that had no equivalent in New Zealand,

Canada or the United States.

Curiously, Clementine Churchill spent a

day (February 7, 1935) in Sydney when she travelled to New Zealand on the motor

yacht Rosaura. After several hours at Taronga Park zoo, she acquired two pairs

of black swans to take home.

Back to list

Back to list