A wonderful, swirling dance of a novel about a community of

lesbian women exploring their inner and outer worlds, and finding ways to live

both as individuals and as part of a larger caring community.

Australian author Finola Moorhead set out to write a different

kind of novel, one that would reflect a how a group of lesbian women were

creating a new style of living that encompassed global travel and the

establishment of a home community in the Blue Mountains of Australia. In her

book, she presents a “feminist aesthetic,” grounded in a nonlinear, rooted web

of connections rather than conflicts. Instead of experimenting with a female

language or use extensive stream-of-consciousness, she has structured her book

to allow a variety of women’s voices to circle and interact using powerful, but

traditional prose. She does not provide a plot about a handful of characters,

but writes a “we” book, featuring a whole group of sharply different women

interacting across global boundaries.

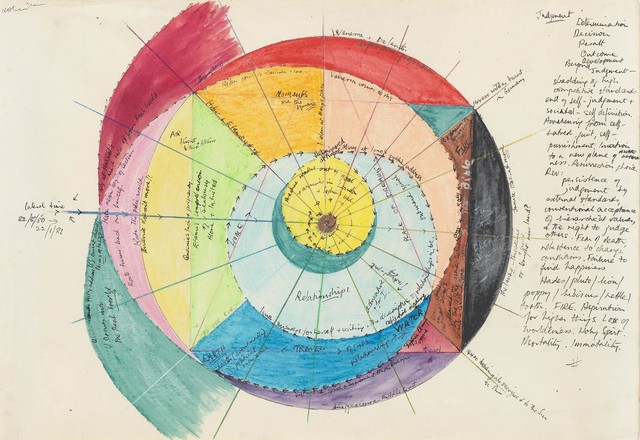

As she describes in her afterword, Moorhead started work on this

novel with diagrams and mathematical drawings of circles and triangles, then

added some nouns and finally text. She structured her writing by using the

zodiac, tarot cards and other more esoteric patterns. Overall, she spent eight

years creating Tarantella, three of

them listening to and incorporating the responses of women readers. First she

expanded her book and then she cut it back. Little of her creative search for

structures was evident to me as I read Tarantella, but somehow she manages to

achieve a unity that underlies a sometimes chaotic and confusing surface. In

addition, Moorhead is a fine wordsmith. The book is filled with sentences and

phrases that I wanted to capture and keep. Her story is often rooted in the

natural world and her descriptions of the Australian landscape are moving. Her

characters, admittedly sometimes strange, are real comprehensible individuals.

Moorhead lists twenty-six women as the cast for Tarantella, one

for each letter of the alphabet. Some are Australian, but others are from

Spain, Switzerland, India, the United States, and Brazil. They belong to

different generations and cultures. Politics and personalities are also varied.

As one woman describes them, they are “a ragged band of beggars trooping toward

the sunset, as clever as gypsies, plucking mandolin strings and blowing mouth

organs, making fires and cooking grains, the sisters, the spinsters marching in

freedom.” Men are present around the edges, able to impregnate and cause damage

but never fully drawn characters in the book.

All are the women are lesbians, and lesbian life is their common

ground. Sexuality is present and taken for grant as important, but not

highlighted. There are no diatribes against men or patriarchy or against women

who choose to be straight. In a rare section near the end of the book, Moorhead

expresses why being lesbians is critical to the women’s lives, but she does so

in political, not sexual terms. As Etama starts to organize a movement against

nuclear weapons and US military bases in Australia, she explores her own

motivation. Viewing men as more willing to encounter death, she explains “But

for women sex is a new beginning. It is new life. Engendering, giving birth,

nurturing.” She was “aching for the new depth, the myth that got murdered,

judged and silenced out of existence, but that’s always been there, the

archetype, Artemis, the lesbian goddess, and the Amazons who were the first

feminist branch of the human family.”

Moorhead does not give equal attention to all her diverse cast.

Instead, she alternates brief chapters highlighting five women, the ones whose

names begin with vowels, treating each with a different type of writing. Etama,

traveling in Europe, writes letters. Arnache, imprisoned in Saudi Arabia,

writes semi-coherent notes, perhaps in the sand. Ursuala, disfigured and

isolated by an ugly scar across half her face, keeps a diary. Iona, a taxi

driver and aspiring author is described in third person. So is Oona, an Aboriginal

woman who had squatted on the land in the Blue Mountains before it was

purchased by the “white dykes” who create a camp there.

The other women move in and out of the story, revealing

surprising interconnections between characters and situations. On one hand each

of the women is on her own journey. As Grunhilda states, “Following your dreams

is a matter of trial and hard work, solitary, thankless and rewarding only in

the eventual, inevitable understanding that, at least, you attempt to take your

destiny in your own hands.” At the same time, all the women are part of a loose

web. Physically, the land at “Moonmares,” is a place of temporary retreat and

coming together, but it functions more as a touchstone than as a permanent,

closed community. The women come together there, or Australian cities, or in

lesbian-friendly households around the world,

Of course there are internal conflicts of many kinds; between

generations, political factions and former lovers. The women, individually and

as a group, face attacks from outsiders. But the book is an amazingly happy

one. When couples break up, partners find someone new to love and be loved by.

Characters put forth elaborate mystical schemes, but no one argues about

theory. Together the women can create an electric atmosphere, “The

conversations move, showing emotions, reactions, point and counterpoint. There

is short story upon short story in the layers of the party, vibration crossing

vibration, swelling into waves and receding into many little endings. Freshness

of intellectual engagement, a spectrum of accents and attitudes from cynicism

to commitment expressed, short of the need for disagreement.”

Just as Moorhead creates a

unique structure for her book, she challenges the way we think about ourselves

as women. She has not written a realistic portrait of a lesbian community, much

less a community that includes a range of sexual diversity. She has not created

a lesbian utopia, but raises questions for which she offers no practical

solutions. What she has accomplished is to challenge her readers’ assumptions

about what it can mean to be a woman and what women need in their

relationships. Moorhead’s characters are fundamentally single and

self-determining but they function within a larger supportive network of other

lesbians wherever they go. They form close loving couples, bound to each other

sexually and emotionally, but those partnerships do not limit their individual

actions and they are not expected to meet all their needs. In other words, the

couples do not function as traditional marriages. Some of the women have ties

to their mothers and other family, which can hold them in painful situations.

Iona, at least, seems to find a way to meet such obligations in ways that allow

her continuing involvement with her close friends. Although the community of

women welcome the birth of a new daughter, Moorhead avoids any real treatment

of how motherhood and children fit into the community she envisions. None the

less, she offers an alternative vision that differs sharply from those who

would claim that woman, and by implication men, have to

choose between individual goals and meaningful involvement in a

supportive family or community.

Back to list

Back to list