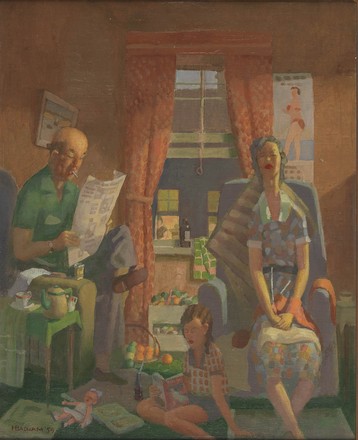

A small painting by Sydney artist

Herbert Badham, recently acquired by the Library, depicts a family of three

relaxing in their living room. Painted in 1959, towards the end of Badham’s

life, Domesticity shows a woman

dozing in an armchair, knitting dropped in her lap. A man reads the newspaper

with a cup of tea and cigarettes to hand, leg raised and ankle resting across

his knee. A child of about 10, probably the couple’s daughter, reads on the

floor between them, her toys scattered around her.

Until recently, when a number of his

works came on to the market and began realising ever-higher prices, Herbert

Badham was a largely neglected artist. Having studied at the Sydney Art School

under Julian Ashton, George Lambert and Henry Gibbons, he later taught at East

Sydney Technical College. He was one of many Australian artists who rejected the

focus on the Australian bush and landscape and embraced instead the modern

city. With the acquisition of Domesticity,

the Library now holds seven of his paintings.

This painting typifies Herbert

Badham’s focus on commonplace subjects, always recorded with careful detail.

His work reconstructs urban and domestic scenes of the mid 20th century.

While Domesticity ’s caricatured style suggests a work of unidentified

sitters, the woman — as so often in Badham’s paintings — is a depiction of his wife

Enid Wilson. The man includes elements of Badham himself. And although she was

in her early 30s in 1959, the girl represents Badham’s daughter, Chebi, suggesting

the painting might be a nostalgic work from memory.

Domesticity records the mundanity and the casual intimacy of everyday family life.

Badham conveys the universal nature of the scene while also indicating its time

and place. Fashion, taste, hairstyles and room furnishings — the walls

unadorned except for a calendar and a framed print — are rendered with detail

and accuracy.

But surely the Library has

photographs to document family scenes such as this. Why do we also collect

paintings? This is a question I have been asked since the acquisition of

Badham’s Domesticity.

With the ubiquity of photography

today, we can easily forget that it was not always so. We capture and post

online not only photographs of significant events but of every outing, every

gathering of family and friends, every meal we’re served. We photograph our

children’s every deed, momentous and mundane, from birth onwards. But this is a

recent phenomenon, not only in the history of visual documentation, but also in

the much shorter history of photography.

In its infancy during the mid 19th

century, photography was specialised, complex and technical. The advent of the

Kodak camera in America in 1888 meant that suddenly, from the 1890s, a large

number of Australians were able to take photographs. Still, even into the 1950s

when Badham created his small painting, it was unusual to photograph people

lounging around in their living rooms, playing, reading and dozing off. These

seemingly inconsequential activities, which bind families together and even

help define them, are the everyday things that Badham documents so well.

Though less posed than the stilted

family photographs produced during the 19th century — when small children and

babies were clamped or held in position in studio settings during the camera’s

long exposure — family photographs tended to have a formal quality even in the

1960s and 70s ...

Before photography, of course, some

of our most intimate glimpses into family life came from artists, many of them

amateurs. One example is a small, incomplete watercolour from the 1840s of the

drawing room at Tarmons, the grand family home of Sir Maurice and Mary

O’Connell that once stood in

Darlinghurst. Painted by an unknown

artist, it shows a group of five people sitting to sew or read, companionably,

either around the draped, centre table, the focus of family life, or in other parts

of the room.

An earlier family portrait, drawn by

Robert Dighton in 1799, shows Philip Gidley King, his wife Anna Josepha and

their children seated around a table. The following year King left England with

his wife and their youngest child,

Elizabeth, to take up the

governorship of NSW.

Until recently, photographs of

families relaxing in their homes were more elusive than drawings or paintings.

A beautiful exception is Joseph Check’s photograph from the 1890s of the Frazer

family of Ballina, in northern NSW, seated around the family dining table

tucking into their meal. Aiming to seem natural, Check’s photograph has clearly

been set up and resembles the King family portrait in its arrangement, with the

dining table cleared on one side to capture the whole family, leaving one young

man sitting awkwardly askew.

Artists have the advantage of being

able to compose the scene in the ‘frame’ of the canvas, while still accurately

documenting their subject. This helps them avoid some of the pitfalls of

photography, especially amateur photography …

Professional photographers often

dispensed with the occupants altogether in order to create beautiful images of

domestic settings. The room itself became the focus rather than the family and

how they interacted within the space.

Artists have had no need to trade

off the background of their image for the sake of the foreground, or vice

versa. In Domesticity Badham has

recorded small background details such as the family’s neighbour, who can be

seen through an open window, standing at the sink washing up. This peripheral

detail in Badham’s painting would have been impossible to capture in a

photograph in the same period.

And while paintings and drawings

have their own preservation requirements, the chemical processes of film-based

photography make deterioration unavoidable. Colours fade and distort — colour

photographs taken before the turn of this century are nearly all on what is called

‘fugitive’ material. Stored in albums that can be harmful, photographs are

often at risk. Even digital prints are not exempt from colour fading and loss

of detail.

The Library’s picture collections

are enormous, certainly the largest in the country. They are also highly varied

in terms of formats, quality and durability. What they have in common is their

documentary value. They illustrate Australian society, landscape and buildings,

and the life and times of Australian people. They are, in a sense,

anthropological in nature. Pictures in the Library collection have been

selected on the basis of the information they contain rather than artistic

merit, yet this information is filtered through an artistic or photographic

eye.

The Library continues to be active

in collecting contemporary documentary photographs, including digital

photographs. But just as the birth of photography did not see the

much-predicted end of painting, the predominance of photography in our culture has

not seen the end of collecting paintings and drawings. The Library recognises

that artists, like photographers, can capture people, places and

ideas, and almost ephemeral impressions, with clarity and directness.

Back to list

Back to list