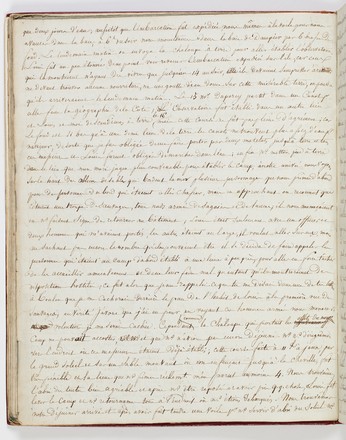

Journal particulier de Rose pour Caroline

Rose de Freycinet Journal (September 1817- October 1820)

SAFE / MLMSS 9158 vol 1

Rose de Freycinet was the young wife of French

naval officer Louis de Freycinet. In

1817 Freycinet was given command of a Pacific scientific and exploring

expedition, as captain of the Uranie. The Uranie expedition was one of the major

expeditions into the Pacific in the early 19th century. The expedition sailed,

via the Cape of Good Hope, to Shark Bay, in Western Australia, before sailing

to Timor, Indonesia, the Caroline Islands, and Guam. The expedition then sailed

across to Hawaii, and then south to Sydney where they stayed for a month in

November 1819. They spent time exploring the townships of Sydney and

Parramatta, with some expedition members travelling as far afield as Bathurst.

The expedition left Sydney Cove on Christmas Day, 1819 but on

the 14th of February 1820 the Uranie struck rocks in the Falklands Islands and the ship was

damaged beyond repair. A three-month wait followed, and finally, they secured a

passage to Rio de Janeiro, and reached Le Havre on 13 November 1820.

Rose kept

two records of the expedition. One was her journal, which she wrote expressly

for her dear friend Caroline de Nanteuil, the other was a series of letters

written to her mother during the voyage.

Disguise & Deception

As captain of the Uranie,

Freycinet secretly planned to take with him his 21-year-old wife, Rose, a well

educated and cultured woman. Because this was very much against regulations,

Rose slipped on board dressed as a man, and stayed in her husband’s cabin until

they had cleared Gibraltar. It seems

clear that some of her family were aware of her plans, and there were certainly

well known precedents. Jeanne Baré had slipped aboard Louis-Antoine de Bougainville’s

1766 world expedition. Baré maintained her disguise for much longer than Rose

who only waited a couple of days to reveal her deception.

It would seem that Joseph Banks may have had similar plans to

smuggle a woman on board the Resolution

on Cook’s second voyage. On Cook’s arrival in Madeira he learned that three

months earlier a ‘gentleman’ of the name of Burnett had arrived on the island claiming

that ‘he’ was waiting to join Banks’ party as a botanist, having been unable to

board the ship in England. Shortly before the Resolution’s arrival, ‘he’ (now widely recognised as a woman)

learnt of Banks’ failure to sail and immediately embarked on the first sailing

ship home to Europe. Cook wrote to the Admiralty saying that ‘every part of Mr

Burnett’s behaviour and every action tended to prove that he was a woman. I

have not met with a person that entertains a doubt of a contrary nature … ‘

(Hough, 1994). Perhaps the mysterious ‘Mr Burnett’ was Mr Banks’ mistress and it

is possible that Banks may have had plans to smuggle her on board the Resolution? However this has never been

proven.

Rose’s journal and letters provide a personal perspective to

a major official expedition. They detail personalities and events in contrast

to the official account published by her husband. Rose’s presence on the voyage

of the Uranie could never be

officially acknowledged and although Rose was included in Alphonse Pellion’s

unofficial depiction of the Uranie camp

in Shark Bay, Western Australia, she was removed from the published official

view.

Shipwreck off Falkland Islands

On 14 February 1820, the Uranie

struck rocks in the Falklands group of islands. The ship was damaged beyond

repair. A three-month wait followed, camped on an island and hoping for a

passing ship to rescue them. A passage to Rio de Janeiro was finally secured.

They reached Le Havre on 13 November 1820.

`I thought that it was all over forever for me, I gave my

soul to God and I despaired att eh idea of the dreadful death that we were

going to suffer.'

Back to list

Back to list