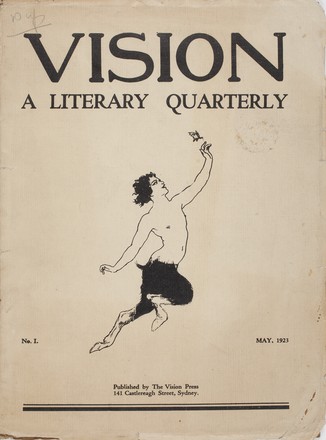

Vision, A Literary Quarterly, May 1923

Printed book.

QA820.5/V

Printed book.

QA820.5/V

“The first 48-page issue of Vision appeared in May 1923 with more than a dozen Norman Lindsay sketches of nymphs and satyrs prominently displayed. Planned as a vehicle for the aesthetic philosophy of Lindsay and to a lesser extent the ideas of poet Hugh McCrae, its editors hoped the magazine would usher in an Australian renaissance to bolster the literary and artistic traditions rejected by European modernists. The editors also believed that the magazine would invigorate an Australian culture they claimed was stifled by the regressive provincialism of publications such as the Bulletin.

Proposed during regular meetings at a Sydney coffee cellar, the magazine was edited by Frank C. Johnson, Jack Lindsay (Norman's son) and Kenneth Slessor. Johnson, an assistant at Dymock's book store, acted as business manager, setting the price of the magazine at 3 shillings and sixpence per copy. He also attracted a variety of advertisers, including Penfolds, Studebaker, Kodak and The Shakespearean Quarterly. Slessor and Lindsay performed the major editorial tasks and provided most of the contributions, including a number of pseudonymous contributions from the latter.

The intellectual programme of the magazine was presented in regular forewords and essays by Norman and Jack Lindsay. Prominent modernists were criticised and often lampooned for their rejection of conventional form and their jaded outlook on modern life. The magazine further asserted its anti-modernist stance by proclaiming 'free verse will not be considered' in its calls for contributions. Proceeding from Norman Lindsay's principles of beauty, passion, youth, vitality, sexuality and courage, Vision consistently provided readers with potentially offensive content. But the editors welcomed any negative attention, stating in the fourth issue, Vision has . . . published a vast amount of material which would have been destroyed in moral fury by any other periodical. It blushes for the compliment.'

The contributions of Slessor and Jack Lindsay were accompanied by the work of a number of other writers, including Hugh McCrae, Dorothea Mackellar, R. D. FitzGerald and Dulcie Deamer. Many of these contributions exhibit the direct influence of Norman Lindsay's ideas. When the fourth issue of Vision appeared in February 1924, it advertised plans for a larger format in the next issue. Promising one hundred pages with illustrations, uncensored material and popular serials,Vision was to appear bi-quarterly at a new price of one shilling and sixpence. But this did not occur and the editorial team of Vision disbanded”.

“Vision 5 never appeared … After its initial success sales began to flag and Johnson thought the magazine’s fortunes would be improved by adopting a more popular, less precious format. It was now to be issues bi-quarterly starting from March 1924, with double the contents at a much cheaper price. But Johnson was unable to raise sufficient finance to achieve the necessary economies of scale and the whole project fizzled. Johnson … from the beginning wanted to increase the visual art content for fear that a purely literary magazine would fail. Johnson’s commercial interest was in any case bounds to be at odds with Vision’s Bohemian contempt for monetary values”.

“The industrious Lindsay continued to support publishing ventures during the following decade. The reconciliation with his son Jack after a long break had brought him in contact with a younger generation of writers and poets who were eager to share Lindsay’s vision of a bright new world. When Jack became friends with Frank C Johnson, an assistant in a Sydney bookstore, the idea of publishing a literary magazine became a reality. The quarterly Vision first appeared in May 1923, edited by Jack, Johnson and Kenneth Slessor. The last issue appeared in February 1924. Lindsay enthusiastically supported this venture, which included contributions from Jack, Kenneth Slessor, Robert Fitzgerald, Dorothea Mackellar and McCrae, among others. As usual with such endeavours, it appears that contributors were not paid. Even with Lindsay providing illustrations, sales were low and the venture failed to attract advertisers and backers”.