The Papal edict of Tordesillas

By Emma Gray, 2014

In 1494 the Papal edict of Tordesillas divided rights to all

newly discovered lands between Portugal and Spain, based on an arbitrary line

running from pole to pole approximately 2,061 kilometres west of the Cape

Verde islands. The Spanish controlled

the area west of the dividing line. They established a base at Manila in the

Philippines and conducted lucrative trade between this new centre and their

colonies along the Pacific coast of North and Central America. Portugal

established successful trading routes between Europe and the East Indies.

In the seventeenth century the Dutch ousted Portugal from the East

Indies and dominated trade and exploration in the region up until the eighteenth

century. Spain concentrated on expanding their bases in Central America, Mexico

and Peru.

During the eighteenth century, other European naval powers,

particularly England and France, began the exploration of the Pacific regions in

search of trading opportunities, strategic bases and the legendary landmass of Terra Australis.

In 1767 as part of a voyage to circumnavigate the world, Captain Samuel

Wallis arrived in Tahiti on the Dolphin

claiming the Island for Britain with the name of King George’s Island. Later in

1767 the island was visited by Louis Bougainville who claimed the island

for France and named it New Cythera. Captain Cook reached Tahiti in 1770 on the Endeavour. Cook called the

island Otaheite.

Spanish activity in the Pacific region had diminished following the

Seven Years War(1756–1763), in which

they lost significant land, including Spanish Florida and islands in the West

Indies to the British. With the increase in British activity and potential

threat to their empire the Spanish Crown launched a series of exploratory

voyages to map and colonise several South Pacific islands, as well as to

explore and claim the American territories inland from their bases in

California and Mexico.

Gonzalez and Boenechea expeditions

By Emma Gray, 2014

The first expedition was by Felipe Gonzalez to claim Easter Island for

Spain, which he did in November 1770. He spent five days mapping the island.

Domingo Boenechea headed the 1772 Tahiti expedition and surveyed the

island, reporting in 1773 that it was suitable for a Spanish colony. The

Spanish called the island Amat’s Island after the Spanish Viceroy. In 1774 Boenechea

returned to establish the colony which was to be led by two Dominican friars. The

colony failed within a year, effectively ending the Spanish empire in the

Pacific.

Although the power of the Spanish Empire in the

Pacific had diminished Spanish interest in Pacific activities remained

significant. Between 1789 and 1794 the Spanish authorised a scientific

expedition by Alessandro Malaspina.

After a survey of the Spanish colonies in America, he sailed across the

South Pacific visiting Port Jackson in March 1793. Malaspina’s Political Examination of the English

Colonies in the Pacific, written on the return voyage, discusses the

potential impact of English colonisation on Spanish interests. Malaspina

concluded that any physical threat should be countered by establishing a strong

market in the colony for goods from the Spain’s American interests.

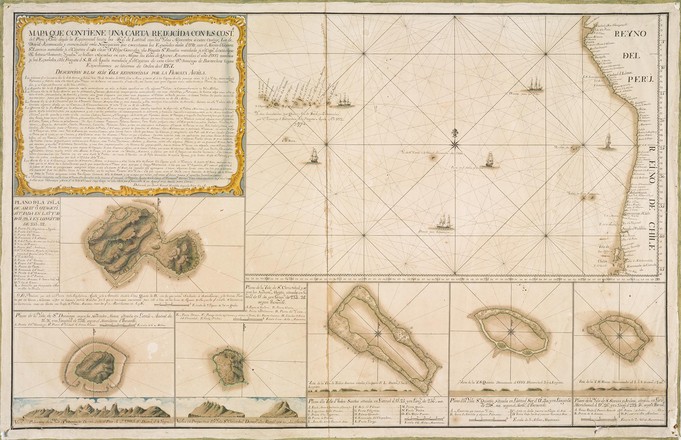

The most detailed known charts of the Spanish expeditions to Tahiti and Easter Island

By Emma Gray, 2014

Although the aims of the Spanish expeditions in the 1770s were

ultimately unsuccessful, the maps which remain documenting the activities and

settlements are significant both for their content and their rarity. The

collection contains the most detailed known charts of the Spanish expeditions

to Tahiti and Easter Island.

In Spain at the time, publishing maps and journals of exploratory

expeditions was subject to strict secrecy and censorship laws. Within a

generation of the expeditions, the Spanish American empire had collapsed, and

public interest in the history of the explorations had waned. As a result,

material known from this period is rare.

The extent of the discovery and charting of Pacific territories by the

Spanish is not as well-known as the English and French voyages. The

achievements of English, French and even Russian voyages charts of exploration

including private journals and charts were published and circulated widely. The

Spanish Government retained a tight control over information gathered from

their expeditions.

Around 1775 the charts in this collection were commissioned and

collected by Commodore Somaglia for his personal use as Commander of the South

Pacific Squadron of the Spanish Armada Real.

Joseph de la Somaglia was an Italian born officer in the Spanish Navy.

In 1770 he was appointed to a post in Callao, Peru as the Commandante de la

Esquadra of the South Sea. Somaglia was

responsible for the outbound security of Spanish vessels carrying silver and

gold to Europe. He also oversaw the expeditions to the Pacific including the

voyages of Domingo de Boenechea to Tahiti and the Polynesian Islands.

From a collection of 24 manuscript charts ...

From a collection

of 24 manuscript charts of the Pacific Ocean and South America, highlighting

the Spanish expeditions to Easter Island and Tahiti, 17623–1775

This

collection was assembled by Commodore Joseph de la Somaglia, Commander of the

South Pacific Squadron of the Spanish Armada Real between 1770 and 1778. The

charts document Spanish activity in the Pacific in the second half of the

eighteenth century particularly, the Spanish expedition to Easter Island under

Felipe Gonzalez in 1770 and two expeditions to Tahiti under Domingo Boenechea

in 1772–3 and 1774–5.

Since the

Papal edict of Tordesillas in 1494 the Spanish had regarded the Pacific as its

exclusive domain. In the eighteenth century this position was threatened by the

expansion of English, French and Russian exploration in the Pacific. In 1774 a small colony was established on

Tahiti consisting of two Franciscan priests. A year later the settlement was

abandoned and Spanish attempts to re-establish their foot hold in the Pacific

were abandoned.

Back to list

Back to list