Hume and Hovell

In 1824, Hamilton Hume and William Hovell led an expedition of discovery to find new grazing land for the colony. They and their party trekked south from Appin to Lake George, then on into Victoria, keeping west of the Great Dividing Range and ending up at Corio Bay, on the Victorian coast, where present day Geelong is situated. (Hovell mistakenly believed they had arrived at Westernport, and did not realise his mistake until after his return.)

Hamilton Hume was born near Parramatta on 19 June 1797. At fifteen, Hume moved with his family to a large grant of land near Appin, and from the age of seventeen began exploring the land south to the Berrima region. He gained a reputation for his bush skills and knowledge of the area and was asked by Governor Macquarie to take part in several inland journeys to Lake Bathurst, the Goulburn area and south to Jervis Bay, with James Meehan and John Oxley. After an expedition with Alexander Berry, Hume was given a grant of land at Appin where he established a farm. He later acquired land in the Yass district, where he set up a second station. Governor Brisbane wanted to have the land between Lake George and Bass Strait explored, but he was unable to finance such a long and difficult expedition. Hume was inspired to attempt the expedition himself, planning a journey to what is now Spencer Gulf in South Australia, but was also unable to finance the trip. A mutual acquaintance, Alexander Berry, introduced Hume to a former sailor, William Hovell, who lived on his own grant of land at Narellan.

William Hovell was eleven years older than Hume. He was born in Norfolk, England, on 26 April 1786. By his early 20s, Hovell’s career at sea was established, and he commanded a trading ship in South America. In 1813, he and his family emigrated to New South Wales where he worked for Simeon Lord, again as captain of coastal and trans-Pacific trading vessels. In 1816, he left life at sea and took up farming on his grant of land at Narellan. Hovell had made short exploratory trips himself, but his real skill was in navigation. He had also been considered for Brisbane’s unrealised expedition, and offered to take part in Hume’s journey and share the cost. The expedition was mostly financed by Hume and Hovell themselves.

To raise the money needed, Hume sold an imported iron plough – a sought-after item in the new colony – and Hovell sold some of his land. They received a small amount of assistance from the Government stores, including six pack saddles, a tent and some clothing for their convict servants. They also took a team of bullocks, several horses, and enough supplies for four months, including, as William Hovell documented:

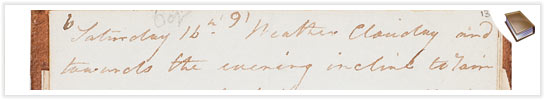

‘640 lbs. [pounds] flour, 200 lbs. pork, 100 lbs. sugar, 14 lbs. tea, 8 lbs. tobacco, 12 lbs. soap, salt, coffee, etc., etc., etc., for myself and three men, together with a musket and ammunition for each man. This is exclusively for ourselves, as Mr. Hume has supplied (as I understand) the same quantity.’

William Hovell, 2 October 1824, Journal, Safe 1 / 32d

On 3 October, 1824, the men left Hume’s farm at Appin. They headed south to Hume’s station at Yass, near Lake George, where the expedition was to begin in earnest. On 17 October, after several days’ rest at Hume’s station, the party set off into areas not yet settled by the Europeans.

> View maps of the journey taken by the exploratory party

The terrain south was difficult. The expedition had to cross several treacherous rivers, including the Murrumbidgee, where, after several days of planning, the bullock dray was temporarily converted into a punt. The Great Dividing Range also proved difficult. The bullocks had trouble keeping their footing on steep, slippery mountainsides, and Hume and Hovell argued regularly about the best route through the mountains. Hovell was older than Hume and probably used to being in charge. He also had extensive navigational experience from his sailing days. Hume, on the other hand, was arrogant, but knowledgeable about bushcraft and the Australian landscape. At one stage, the expedition split in half, because the men could not agree on the direction to follow. Hovell soon rejoined Hume when he realised that his partner was right, and the expedition proceeded in a relatively friendly fashion. Ironically, most of the credit for the expedition went to Hovell, as the older partner, but it appears now that Hume may have contributed more to the success of the expedition, thanks to his superior knowledge of the Australian bush.

> Read more about Hume and Hovell’s journey and their discoveries in Hovell’s own journal

On their return, in January 1825, Hume and Hovell reported their discoveries to Governor Thomas Brisbane. A party (including Hovell) was sent by sea to Westernport to re-examine the fine land which Hume and Hovell had described, and it was then that Hovell realised that the two men had journeyed to Corio Bay in Port Phillip, not Westernport, as he had previously thought. Despite this error, Hume and Hovell's expedition opened the way for settlement around the Port Phillip area, resulting in the founding of Melbourne.

Both Hamilton Hume and William Hovell were rewarded with large land grants for their work, but later a bitter dispute erupted between the two men over their respective roles in the expedition. In an 1853 visit to Geelong, Hovell was celebrated as the discoverer of the region and the press reports enraged Hume, who thought that Hovell was claiming sole credit for their discoveries. Both men published pamphlets giving their versions of the expedition, and Hamilton Hume remained embittered until his death in 1873. William Hovell died in 1875.

The South Australian Alps as first seen by Messrs. Hovell and Hume on the 8th November, 1824, c. 1837-1870, by George Edwards Peacock

Oil painting ML 144

'At the end of seven miles a prospect came in view the most magnificent. This was an immensely high mountain covered nearly one-fourth of the way down with snow, and the sun shining upon it gave it a most brilliant appearance. It was surrounded by other irregularly formed mountains, but they did not appear to have any snow upon them on the north side, nor were they so high as the former. The supposed distance is about fifteen or twenty miles. From E.S.E. to S.W. was one continuous range of the highest mountains I have seen in any part of the colony'.William Hovell, 8 November 1824, Journal, Safe 1 / 32d

Captain

Captain Hamilton Hume, explorer,

Hamilton Hume, explorer,